By Kat Montgomery

ACROSS the street from Clary’s Diner sits a pair of beautiful blue doors that have since been painted some nondescript door color. My friend and I, waiting for a table at Fox & Fig, walked down to take a picture with the beautiful blue doors, and as we posed and twirled and laughed, two people emerged from another set of doors directly beside us.

Our two groups startled each other. “Sorry,” they said, “we didn’t expect anyone to be standing right at our door.” A little embarrassed to be caught mid-Vogue, we expressed our love for the teal-colored doors and asked if this was their home.

“Oh no,” they said. “This is an Airbnb, those are doors to the patio space.”

Some magic was lost after that encounter, like when you see a stately old home that’s been converted to a law firm. I’ll blame naïveté that I assumed apartment-looking buildings were apartments where Savannahians lived, laughed, loved.

But no, actually many buildings in the downtown and Starland area are Short Term Vacation Rentals (STVRs) listed on sites like Airbnb and VRBO. A quick search of available Airbnbs in Savannah boasts over a thousand STVRs, ranging from one-bedrooms to full homes advertised as party houses for the perfect bachelorette weekend.

Comparing the map of available, let alone affordable, rentals on Zillow and the number of registered STVRs is dismal at best. A quick Zillow search shows only 164 rentals from the Savannah River to the Southside, past Hunter Army Airfield.

Savannah’s affordable housing crisis is nothing new, but in the after effects of the pandemic, the market is more grim than ever. The Savannah Morning News reported back in February that rents have risen 32% across the city while wages have not (looking at you, landlord who raised my rent this year). Residents are in great need of affordable housing options. But it’s more lucrative for landlords to pimp out their properties in service of the tourism industry than rent to permanent tenants.

While the historic* Downtown District has been remodeled for the interests of the tourism industry, the Starland District remains an area in flux, caught between serving the interests of locals, students, and tourists alike. In the short seven years I’ve called Savannah home, Starland has had a glow up: restaurants, apartments, breweries, stores that sell specialty sprinkle kits, all shellacked in an Instagrammable coolness.

At the rate it’s growing, what will this area become? Who is the target market for the businesses and housing options in this emerging sector?

*Savannah is in danger of losing its designation as a Historic Landmark District —maybe stop building so many hotels, Kessler? Do you own stock in the neon sign and fake plant industries or something?

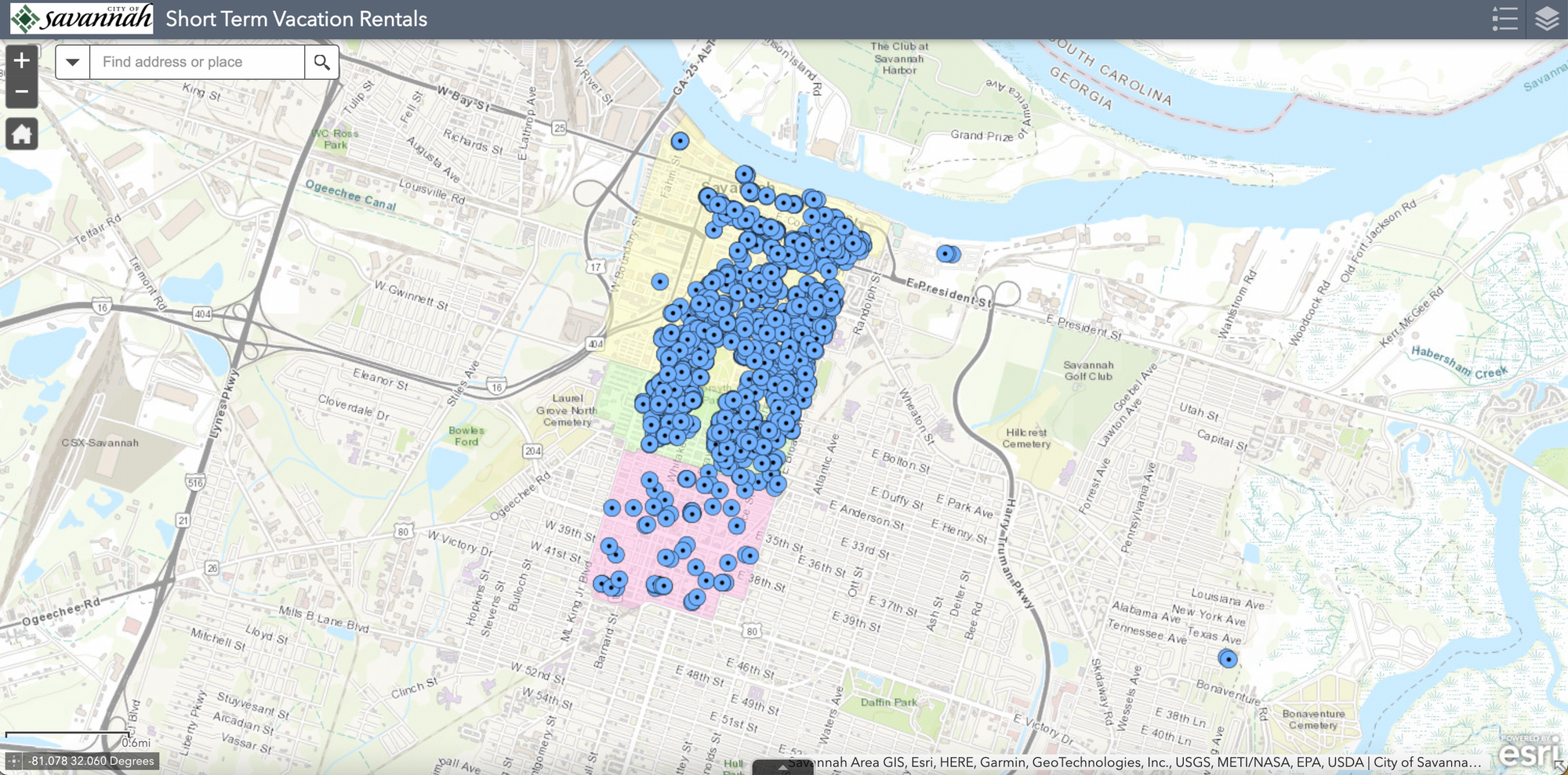

The map of Savannah’s registered STVRs unsurprisingly shows a heavy concentration in the Downtown and Victorian districts, as those areas are closest to where tourists want to go and are also the primary areas where the City legally allows them. But I was shocked at the small sample shown for Thomas Square.

From the friends I’ve known who were kicked out of their apartments so the listing could be changed to an STVR, to the locals I’ve heard bemoan in bars the lack of community on their blocks due to STVRs, to my brother’s neighbor saying to him, “Hey man, I list the place on Airbnb but the city doesn’t know, I’ll cut you in for not ratting on me,” the issue has to be more complicated than what’s shown on this map, right?

Short answer: yes, it is more complicated.

To understand the impact of STVRs on the Starland District, I spoke with Jason Combs, Thomas Square Neighborhood Association President, and Ryan Madson, Victorian Neighborhood Association President, on a breezy May afternoon over a round of Modelos with limes at Over Yonder.

Though both boroughs have different rules surrounding STVR permits, they face the same problems—STVRs disrupt local life in some not-so-obvious ways. Combs and Madson cited residents exasperated by “party houses” causing a commotion, leaving litter, and jamming up the already precarious parking situation in these neighborhoods.

The City of Savannah does have STVR regulations in place. The Victorian Neighborhood has the same permit rules as the Historic District—a 20% cap on STVRs—while Thomas Square has more restrictive rules: STVR listings must be owner-occupied in residential areas in the hopes to quell a lot of the noise complaint issues stemming from STVRs.

Combs points out that while the city does take illegal STVRs seriously*, there aren’t enough employees in Code & Compliance to track every single listing and investigate every single permit, especially when the permit requirements are easy to fake.

Combs mentioned a Thomas Square listing that seemed to check all the permit boxes. The owner claimed to live in the carriage house on the property, when in actuality a SCAD student rents the carriage house while the main house is used as an STVR (which, surprise, garnered complaints from locals because of the noise).

* It’s worth mentioning the City of Savannah gets a tax kickback from all STVR hosting sites for each listing, even illegal listings operating with no permit. Is it really a priority to track these down when these listings provide revenue? Who’s to say.

More than being a neighborhood nuisance, STVRs diminish the sense of community for Starland locals. Combs and Madson have both lived in Savannah for more than 15 years, and their insights into Savannah then versus now should be used as a cautionary tale for the Starland District’s fate.

“Locals don’t feel welcome downtown,” Madson said. “Before, tourists and locals coexisted. But now, locals have been priced out of their own city.”

The best case scenario for STVRs is going back to what these sites were created to do originally: provide additional revenue for those with extra space in their homes and allow travelers to book overnight stays at cheaper rates than hotels.

After our chat, Combs showed me his beautiful two-story home off Lincoln Street where he hosts Airbnb guests. This is the Lawful Good of STVRs: a homeowner with extra space who takes time to create helpful guides so tourists can respectfully visit the city.

But the majority of STVR owners don’t live on site, and many don’t even live in Savannah. Websites like Biggerpockets and AirDNA do the legwork for real estate moguls to find prime properties to flip to STVRs.

It’s unlikely the city could curb these investment sharks without owing a riverboat-load of money to those investors due to a boring legal term called regulatory takings, which occurs when governmental regulations limit the use of private property to such a degree that the landowner is effectively deprived of all economically reasonable use or value of their property.

Now for the hard part of the story: what do we do about this? Underneath all my snark around STVRs lies an ugly truth: I like them. When I travel to other cities I book through Airbnb. I try my best to find listings that look to be in someone’s actual home, but I’ve been duped before.

I’m culpable in this, as are the tourists who unknowingly book an STVR that used to be someone’s apartment, as are the homeowners who kicked out their tenants to convert the space, as is the City of Savannah for letting it happen.

STVRs are like Virginia Creeper vine winding up the brick of my apartment, over my second-story windows, into my open balcony : running rampant and, without intervention, will swallow the building whole.