A CONTROVERSIAL proposed development on a downtown lane – dubbed a "McMansion" by critics – is renewing concerns about the already-threatened National Park Service status of Savannah's iconic Historic District.

The ornate new three-story residence planned for 336 Barnard Street would be built in a subdivided lot directly behind a similar-size historic building overlooking Pulaski Square. It would replace the four one-story affordable housing units that are now on Charlton Lane, and almost completely eliminate the existing courtyard space.

Adding to the controversy is the way the as-yet not finally approved residence has already been listed as for sale on Zillow for nearly $4 million – before those existing accessory dwelling units on the site have even been demolished.

"There's not much infill left downtown. The lanes are pretty much it," says David McDonald, President of the Downtown Neighborhood Association (DNA). "That's where developers are looking now, and that's where we have to fight them."

It's exactly the type of development the National Park Service (NPS) pointed out in 2018, when it officially downgraded the status of Savannah's National Historic Landmark District to "Threatened," two slots down from its previous "Satisfactory" status.

That round of headlines a few years ago came at an especially sensitive time, with local outrage building against out-of-control development in downtown Savannah. The topic would become a hot one in the mayoral election the following year, which brought an almost complete changeover of City Council.

The way our squares, lanes, and streets work together to form a harmonious civic entity is the one single, specific thing you can point to that makes downtown Savannah literally like no other place in the world.

As the NPS writes, "The Savannah Town Plan has been cared for and maintained for generations since it was designed by James Oglethorpe in the 1730s. The plan is part of the Savannah National Historic Landmark District, is central to the city's historic identity and on-going cultural and economic vitality, and is an irreplaceable part of American History. Its preservation is in the interest of the entire Nation."

McDonald says simply that "the integrity of the lanes is really at the heart of the Oglethorpe Plan."

In its official assessment explaining the status downgrade, NPS wrote that one of its chief concerns was the growth in "Alterations, disruption, and/or closure of historic lanes and other public rights-of-way."

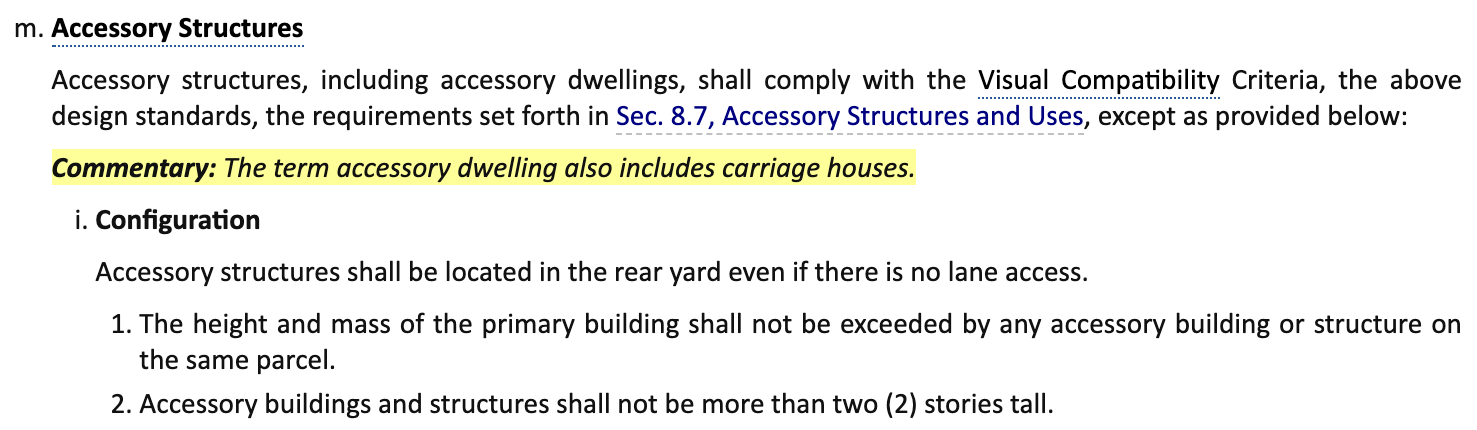

The idea is that accessory buildings – often called "carriage houses" but used for much more diverse purposes, including affordable housing – should remain separate, smaller, and distinct from the main buildings they share a lot with.

"Common sense, public policy and the Oglethorpe Plan demand that new construction at 336 Barnard Street must be a carriage house with parking below and an affordable housing unit above," says Andrew Jones, one of many critics of the planned development who have voiced their objections, so far to no avail.

Other neighborhood critics of the project, Paul and Caren Cobet, say in a written letter to the Historic District Review Board of the Metropolitan Planning Commission (MPC):

"We object to the recent Zoning Administrator's determination that appears to exempt the 336 Barnard Street development plan from the 2 story limit on new structures in the lanes... In our opinion, allowing for more than 2 story structures in the lanes alters and degrades the historic character of the lanes and the Historic District as a whole."

Indeed, the proposed new building seems to flout several provisions of City zoning in the Historic District:

1) Its three-story height is higher than the current allowed height limit of two stories for accessory buildings on a lane. (The developers initially asked for four stories, and the four-story plan is what's being marketed on Zillow.)

2) The mass of the new building seems to clearly defy visual compatibility standards for the Pulaski Square area, though regulators disagree.

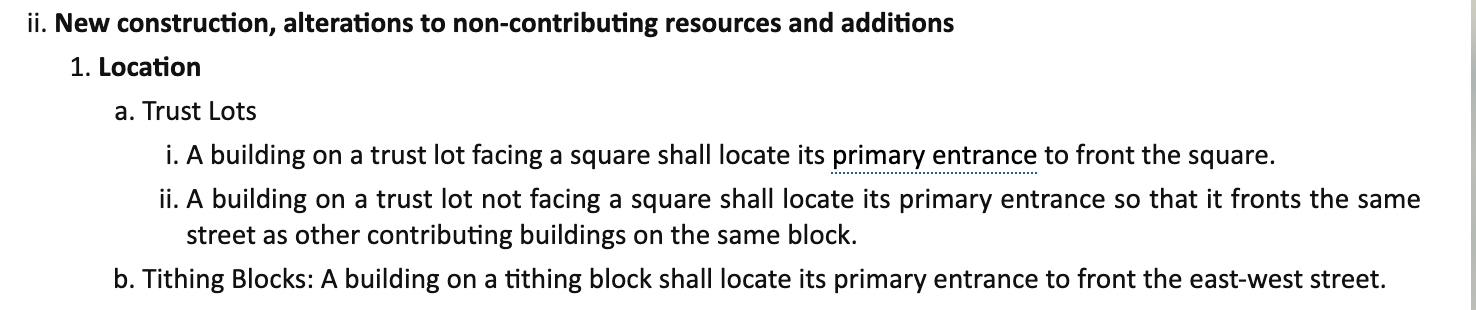

3) And the entrance – planned on 336 Barnard Street instead of the lane – is also against ordinance and the Town Plan.

The lot targeted for development is in what's called a "tithing block," a term going back to Oglethorpe's time. It signifies residential development on the north and south sides of downtown squares.

(The east and west lots are called "trust lots." Back in the day they were intended for more public spaces such as civic buildings and churches.)

The City's own zoning ordinance for the Historic Overlay District specifically says that no principal building on a tithing block can have its address on a north-south street – which in this case would be Barnard Street.

The MPC's interpretation of the zoning administrator's ruling is as follows:

"Sec. 7.8.10(g)(ii)(1)(g) exempts those parcels that cannot locate the primary entrance on an east-west street from the requirement," writes MPC Historic Preservation Director Leah Michalak.

"It is the determination of the zoning administrator that any proposed construction on a tithing block may locate the primary entrance on a north-south street when location on an east-west street is not possible provided it is consistent with contributing buildings within the context."

Translated, the determination is essentially saying that if a developer can't obey the ordinance, they're exempt from having to obey the ordinance.

As critics have said, it's like telling the IRS that you don't have the money to pay your taxes – therefore you don't owe the IRS any taxes.

Critics say this could set a precedent that could result in many more attempts to build oversized buildings directly on downtown lanes.

"They never should have allowed that lot to be subdivided in the first place," says McDonald. "The sad part is the rules allow it for now. The process is bad."

McDonald says he's hopeful that future talks planned with the MPC will result in tightening up the current language in the ordinance regarding buildings on the lanes, disallowing subdivision of tithing lots and keeping lane structures at two stories or no taller than 25 feet.

Based on all the above apparent problems with the plan, Jones petitioned an appeal of the MPC Zoning Administrator's ruling on the applicability of the rule disallowing a front entrance on a north-south street. But just two days before this week's scheduled Historic District Review Board meeting, Jones's appeal was denied on the basis of lacking standing.

With affordable housing an increasingly hot-button issue, the topic of buildings on the lanes has become even more relevant.

And in downtown Savannah, carriage houses, aka accessory dwelling units, are traditionally a haven for affordable housing.

"We want more affordable housing downtown, and we have argued strenuously for that," says the DNA's McDonald. "There needs to be a place for the people who work downtown to also live downtown. There are too many short-term rentals, and too many equity firms buying up property and immediately raising the rents."

The City of Savannah, McDonald says, "talks a lot about affordable housing, but doesn't do very much about it. They didn't address affordable housing with the building going up on the police lot, they didn't address it at East Broad and Liberty, for example. They could make affordable housing a requirement, as other cities have done."

The issue of building on lanes might seem trivial in light of so many other out-of-scale developments that have already been approved in the Historic District, and which have contributed to the downgrade in NPS status.

But as the NPS itself says, overdevelopment on lanes and the demolition of carriage houses is in and of itself a dire threat to the Town Plan.

In the second paragraph of its official report, under the heading "Threats to the Plan," the NPS specifically mentions the degradation of historic lanes:

".... much of the growth that has occurred in the district has been in the open space between buildings and their corresponding lanes. Often the only undeveloped area on many lots, this has led many to build additions in these spaces for additional living space and the integration of elevators," the NPS writes.

"The greatest culprit has been those additions which connect street facing residences with their associated carriage houses. This interrupts the house-courtyard-carriage house rhythm and east-west sightlines of continuous courtyards visible from north-south collector streets," they say.

"To maintain integrity of the District the legibility of the Savannah Town Plan must be retained, a visitor to the District should be able to identify all the elements that compose the Savannah Town Plan (trust lots, tything blocks, squares, and streets and lanes)."

Or as Jones puts it, "The support of the MPC for replacing the existing affordable housing units with an ersatz luxury McMansion flies in the face of multiple civic priorities."

The plans for 336 Barnard Street are scheduled to come up for discussion and vote this Wednesday, Sept. 14 at the regular meeting of the Historic District Review Board, 112 E. State St., at 1 p.m.

UPDATE 9/16: The Historic District Review Board did approve the plans for 336 Barnard Street as petitioned by the developer. However, The Savannahian obtained this memo regarding the outlines of future discussions as the appropriateness of subdividing tithing lots downtown: