SOMETIMES, a musician at the very end of their career will embark on a disappointing “farewell tour” that is little more than a ritualized last chance to pay homage to memories of better times and better performances.

However, Buddy Guy’s headlining Savannah Music Festival performances this past weekend at Trustees’ Garden were not examples of this kind of farewell tour!

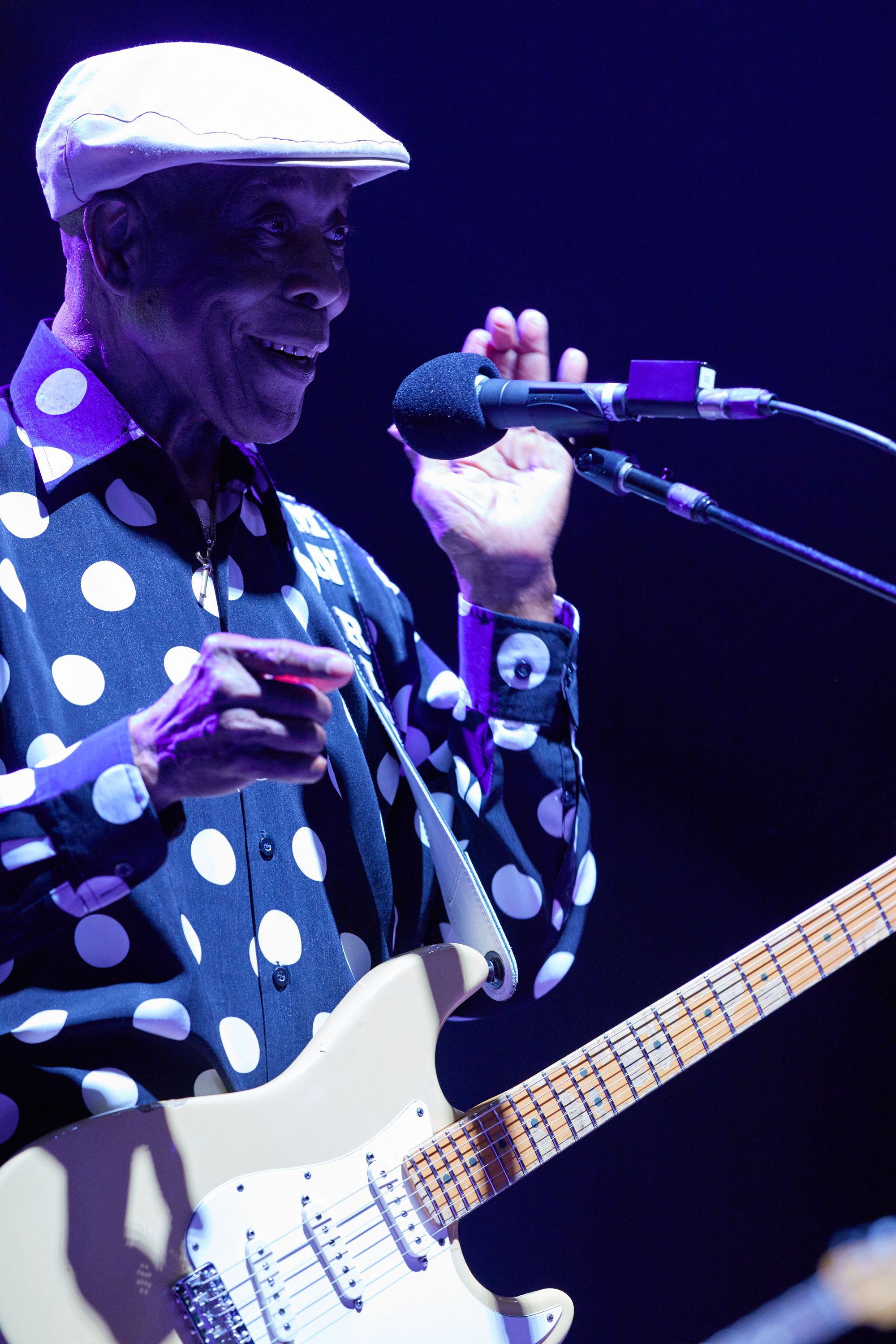

One of the last surviving great legacy bluesmen, an incredibly hale and hearty 86-year-old Guy stalked the outdoor stage like a predatory cat, flinging out filthy blues licks like a machine gunner, dropping casual F-bombs, using a drumstick as a bow, and telling time-tested stories like an old-school comedian.

In short, after opening with his signature tune, “Damn Right I Got The Blues,” this was a career retrospective of sorts – a veteran pulling out all the stops, dominating the stage like a man 60 years younger, pouring out his whole bag of tricks, almost all at once, for a rapt audience to enjoy.

While it was essentially the same stage show Guy's been doing for years, including most of the stage patter... who cares? Guy always delivers the goods, and everyone at Trustees' Garden knew they were in for something special – possibly for the last time ever.

At one point, the retrospective becomes literal with Guy's typical “medley," mashing together bits of B.B. King’s big hit “How Blue Can You Get” (aka “Downhearted”); "Hootchie Coochie Man," a Willie Dixon tune popularized by Guy's Chicago Blues mentor Muddy Waters; Al Green’s “Take Me To The River"; and a tantalizingly too-short version of Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile” – which if Guy had continued playing for 20 minutes, as Hendrix used to do live, would have been worth the cost of admission alone.

Seeing Guy cover Hendrix, it struck me that the two were essentially contemporaries – if he had lived, Jimi would only be six years younger than Buddy. And watching Guy absolutely shred the shit out of a Stratocaster brought home the analogy even further.

The Hendrix shoutout wasn’t a stretch, as Guy has always had a nastier guitar tone than many more marketable blues artists ("so funky you can smell it," as he says), such as the abovementioned King with his smooth caramel tone.

At this performance (as well as frequently throughout his career), Guy commented on how radio basically ignores the blues and bluesmen, even though most rock ‘n’ roll is explicitly based on it. In talking about Hendrix, Guy gave credit, as he often does, to the British listening audience and to UK musicians such as the Rolling Stones – who appreciated the greatness of American blues while it was mostly disregarded and devalued at home.

That said, there’s a certain liberation in not having to worry about marketability, and Guy makes the most of it. His stage patter is uniquely his own, a combination of Redd Foxx-style raunchiness, Borscht Belt corniness, and lovable good-heartedness.

He comes across like your cranky but charismatic old neighbor who you’d love to have a beer with. Oh, and who can also absolutely destroy an electric guitar.

Buddy Guy encapsulates the seeming paradox at the core of the blues, i.e., how can a music based on, and literally named after, sadness be so damn much fun?

But of course, that’s the whole point: The transcendent triumph of the human spirit over adversity.

The highlight for most attendees was the patented “walkaround,” with Guy leaving the stage and venturing a good ways into and through the adoring audience, playing a guitar solo the entire time.

Guy’s return of that adoration was evident. This is a man who literally lives for playing in front of an audience.

While this two-night SMF stand was billed explicitly as part of Guy’s “farewell tour,” the man himself didn’t seem to take that very seriously, at one point saying point-blank he’d continue playing for as long as he is alive.

But the audience surely knew that when Buddy Guy is eventually gone, the old bluesmen will be almost all gone, too. That generation of Depression-born, mostly Southern Black men who helped birth rock ‘n’ roll – but barely made a dime profiting from it – will be a fond memory. “Greatest Generation,” indeed.

As a nod to this impending handoff of the blues baton to a newer generation, Guy closed the show by inviting several younger bluesmen – including his son, Greg, who plays in his dad's band – to take turns soloing after the old master had already left the stage for good.

The visual acknowledgement of the inevitability of the passage of time – and the ability to triumph over it – was unmistakable.