Photos by Marsalis Eason

By Rachael Flora

ON Saturday, August 5, 23 workers from Foxy Loxy, Henny Penny and Fox & Fig went on strike. Later that afternoon, ten were fired and banned from the properties.

It was the culmination of an intense two weeks for the local café chain: on July 21, about 40 employees delivered a demand letter to management of the three cafés, asking for “better working conditions, higher wages, and a safe workplace.” (Neither location of Coffee Fox—on Broughton Street and on Louisville Road—participated in the unionization effort. The coffee bar inside the Gingerbread House, which Foxy Loxy owns, is a satellite bar staffed by Foxy Loxy employees.)

In the two weeks that ensued, Foxy Loxy chain owner Jen Jenkins did not respond to the demands and sent a letter on Slack telling employees that they could bring concerns directly to management. In an interview with The Savannahian, Jenkins and director of operations Julie Kaufman said that they did not receive any of these complaints before the letter, and that the issues as described were not accurate.

But Saturday’s strike was also the culmination of a simmering distrust of Foxy’s ownership. After the video of the demand letter delivery spread across social media, lots of former workers spoke up against the ownership, seeming to corroborate many of the complaints raised in the demand letter—and that management did know about them.

The ensuing two weeks have been divisive, to say the least. For supporters of the Foxy chain, the unionizing workers were young and entitled, unfamiliar with the way business works and making unreasonable demands of a small business. For supporters of the unionizing workers, Foxy management was out of touch and expanded too quickly to support their team.

As with most controversies, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. We spoke with Foxy Loxy’s ownership, the leader of the union effort, and a dozen current and former employees to learn more about what’s going on.

When she first heard about the union forming at her restaurants, Jenkins was on vacation—her first in ten years, she says.

“I left on a Monday, and on Tuesday I get a message from a barista here saying, ‘Hey, Jen, someone is starting a union here, and I don’t know what that means for the future of Foxy. They kept standing in front of me, so I signed it, and I’m so sorry,’” recalls Jenkins. “That’s how I received the news.”

That would have been Tuesday, July 18. On Friday, July 21, the demand letter was presented to management. The unionizing members gave Foxy management two weeks to respond to their demands.

Both Jenkins and Kaufman are adamant that none of these complaints were brought to them before the demand letter was presented.

“We’re here every single day, and we attend all-hands meetings, and I attend all of the shift lead meetings that are once a month, so I mean, I’m a very present and available owner,” Jenkins says. “I know Sam has been saying that they’ve been bringing these issues up to us for months, and the only time I’ve had a one-on-one with Sam is when they said they wanted to interview me.”

Sam Hughes is the lead organizer of the union effort. They have been at Foxy for nine months and works several positions, but is primarily a prep cook.

“The demands that feel the most important to me and my team is a livable wage,” Hughes says. (The employees at the three restaurants have different issues but chose to stand together to demand better for everyone.)

At Foxy, front-of-house employees start at $10 an hour. Through training and promotion to shift leads, hourly wages top out around $14 an hour. Back of house employees start at $12. The tip share is different across all the cafes, but at Foxy, front-of-house gets 70% and back-of-house gets 30% of the pooled tips.

“The biggest thing we would like to change here at Foxy is the starting wage of $15 [an hour], no matter what the tips are,” Hughes says. “So if it’s a slow season, then our wages would reflect $15 every time.”

The service industry is notorious for its unsteady income, and even more so in Savannah, where SCAD’s quarters are clear busy seasons. During the school year, the line at Foxy is out the door; during the winter, it’s much slower. It’s hard to save money when wages are low, so the slow months are a tight squeeze for many service industry workers.

Georgia’s minimum wage is $5.15, so low that the federal minimum wage of $7.25 must supersede it.

The chain’s rapid expansion seems to be a major sticking point for people when talking about wages: in May 2021, Jenkins bought the Gingerbread House, a historic home next to Foxy Loxy, for $1.85 million.

A year prior, in January 2020, Jenkins opened the second Coffee Fox location, which also houses its roaster, on Louisville Road.

This is what people most frequently point to when talking about Foxy’s finances: how could Jenkins not pay her workers more if she can afford to expand to more locations?

In Jenkins’ eyes, more locations means more revenue, and the idea that she close some to pay workers more is ludicrous.

“There’s revenue coming into one. How are you going to move revenue from Fox & Fig or Henny [Penny] to Foxy?” she asks. “That’s such a crazy idea; that financially makes zero sense.”

Raising prices is also an option, but Jenkins is hesitant to do it again because of backlash to previous price raises.

Another demand is that managers stop taking tips. Hughes says that Foxy’s current kitchen manager makes $24 an hour plus tips, whereas former managers only made about $15 an hour.

“To still be taking tips doesn’t make a lot of sense to us,” Hughes says.

But Foxy Loxy management refute that claim, saying they have more control than that. “She reviews every single payroll,” Jenkins says of Kaufman, “and all the credit card tips are paid out through payroll, through direct deposit.” Managers distribute cash tips at the end of each shift.

Hughes says they are also asking for a fair grievance process.

“There have been people with physical and mental disabilities be suspended or fired at my cafe,” Hughes says, “and I and my team would like to see an end to that permanently.”

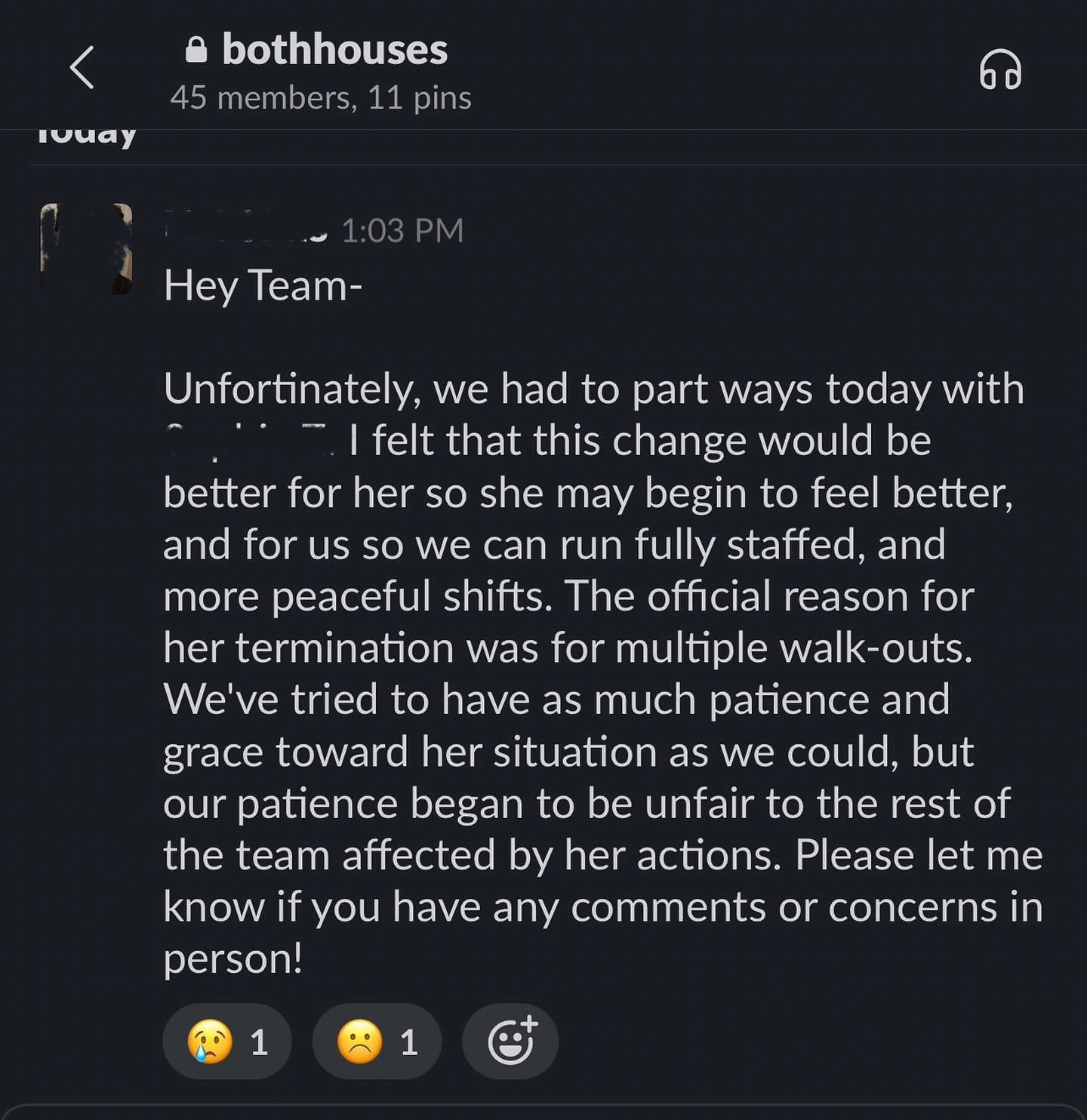

One former employee, Sophia Zeiders, told The Savannahian about her wrongful termination after experiencing two medical emergencies while working. She went to the emergency room twice. When she came back to work, Jenkins and Kaufman told her to go home and that they’d talk later, but she found out she was fired that night via a screenshot in the Slack channel. She filed an EEOC complaint, which was unsuccessful, and has now sued the company.

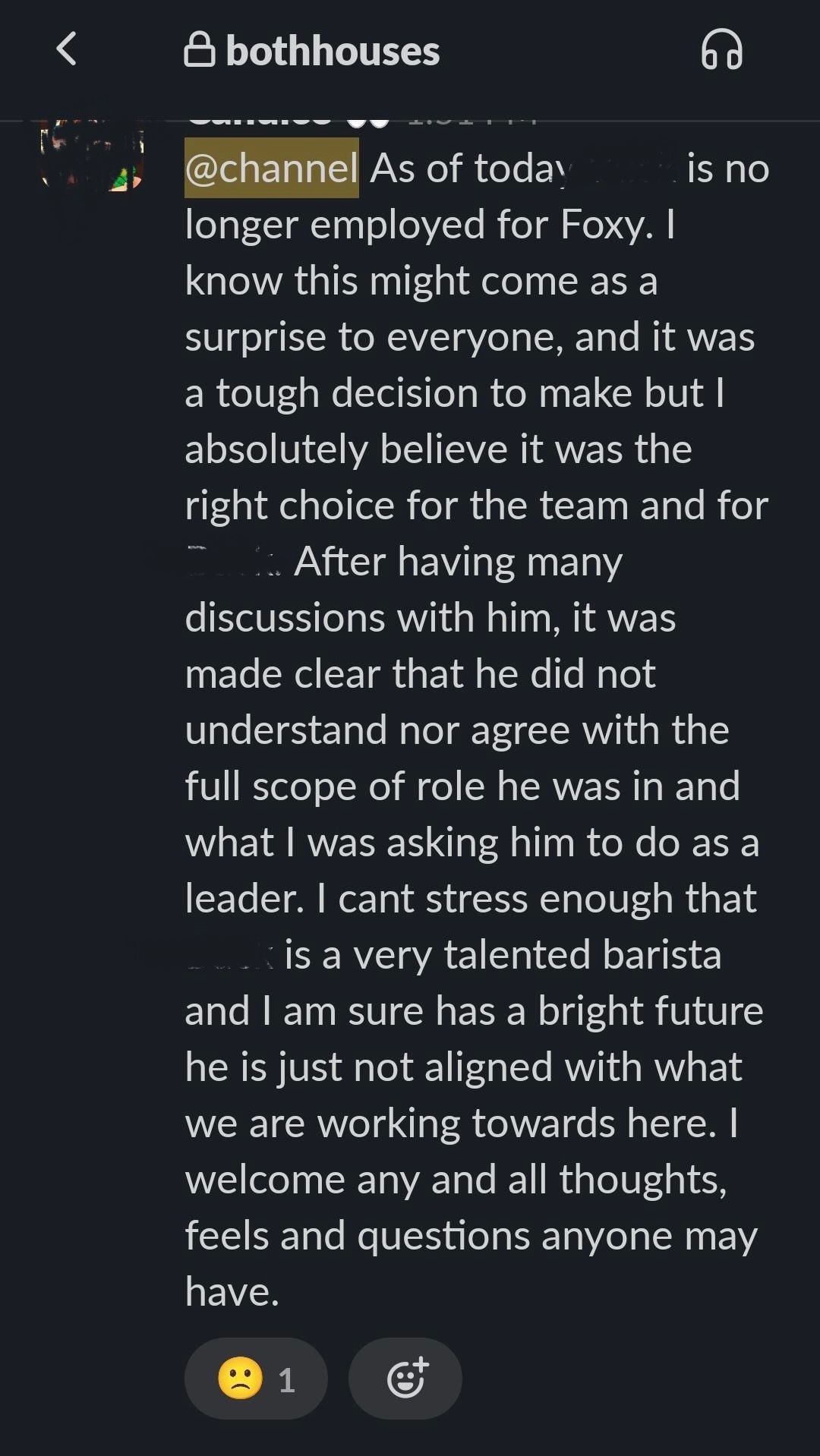

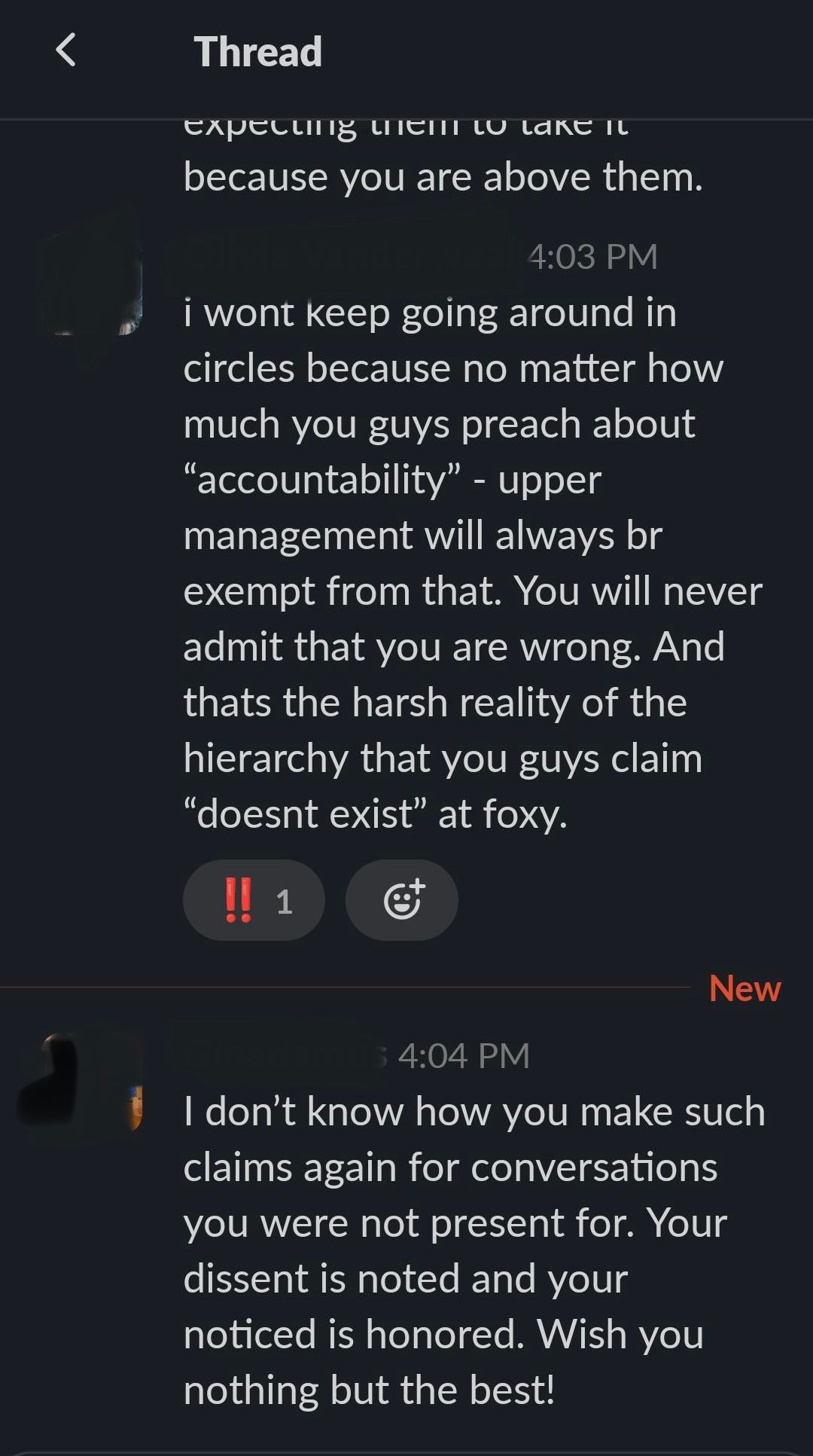

The Savannahian has also reviewed screenshots of the Foxy brand’s Slack channel showing employees being fired in real time and managers discussing the rationale behind terminations.

The Savannahian also heard from other former employees who were removed from the Slack channel or taken off the schedule indefinitely after suffering health issues at work. One worker described passing out while in line to buy food, and one described needing to step away but being told to get back on the floor. Both were taken off the schedule afterwards.

Other demands on the letter include giving employees more decision-making power about their working conditions, corporate accountability, and more consistent scheduling.

A specific ask for Fox & Fig is working air conditioning; the AC has reportedly been broken for weeks, which is uncomfortable and potentially dangerous in summer heat. The kitchen sometimes goes above 90 degrees. Jenkins says the reason for the holdup has been trying to get a quote for repair, and that the restaurant is open enough to keep it cool.

This is apparently not unique: One former Fig employee says that they would work for weeks in previous summers without AC.

Much has been made about the workers’ claims that their workplace is unsafe. Hughes says that while issues are different at each café, the safety issues are mainly from Fox & Fig. The non-functioning AC is the chief safety concern.

“There’s also been some safety issues at Fox & Fig regarding different repairs that took a little too long to be repaired,” Hughes says. “At one point, there was a hole in the ceiling. Technically there still is a hole in the ceiling, but now it has a bit of a cover on it. But for a long time, it was not closed. At one point, they were painting the inside of the restaurant for several days, with a full staff working in the kitchen. So I mean, working in paint fumes trying to serve food isn’t exactly ideal and doesn’t make anybody feel too safe.”

A former kitchen worker at Foxy Loxy shared that they saw plenty of safety issues when they were there. “The kitchen is very cramped and there’s literally no room for safety to be neglected in the way that it was,” they told us.

Hughes and their fellow unionizing employees had high hopes for a peaceful conflict resolution.

“Our owner is a wonderful person who is very reasonable, and I feel like they would be willing to have open and honest conversations if they knew how important this restaurant was to us, and how much our community matters to us,” Hughes says.

Those open and honest conversations never happened. Jenkins says she didn’t feel that the demands were specific enough to her cafés to dignify a response.

“I really feel like all of this is just printed out, and they’re like, ‘Let’s run with it,’” Jenkins says. “And it’s not, ‘These are our specific demands that we’re concerned about in our workplace,’ because it was just online … I’m left here just like, ‘What are they talking about?’”

Hughes and the rest of the unionizing members are working with the Union of Southern Service Workers, which formed last November out of Raise Up, which is the Southern branch of the Fight for $15 and a Union movement. The Service Employees International Union supports these movements.

The USSW is focused on direct action and aren’t interested in the typical structure of labor unions; they didn’t file with the National Labor Relations Board before forming.

Jenkins and Kaufman say that they felt there was no way to make these changes in two weeks, especially since they don’t feel the demands are specific to their workplace, so they did not respond to the demand letter.

They did send a letter to their team via the company Slack channel, a copy of which The Savannahian obtained, advising employees that they did not need a union.

The letter reads in part: “I understand that conversations about unionization are taking place. We fully respect the rights of employees to explore union representation. However, I want to be clear: We do not need a union, with its fees and dues for employees, coming between us. We believe that keeping a direct relationship between the company and our employees is fundamental to the well-being of employees and our business that we have built together.”

While Jenkins and Kaufman are adamant that they were not presented with these issues before the demand letter, other employees suggest otherwise. The Savannahian spoke with multiple employees, both current and former, who say that upper management, if not Jenkins and Kaufman themselves, was aware.

“I know for a fact other people have spoken about things on the demand letter directly to management multiple times,” one current Foxy employee says.

The management team at Foxy is not just Jenkins and Kaufman; management underneath them has experienced high turnover lately. Hughes estimates that Foxy has gone through four kitchen managers and four GMs in the last nine months. Based on screenshots of the Slack channel, employees do not trust the recent string of managers.

Jenkins and Kaufman acknowledge that one recent manager may have been the sticking point for some employees.

“There was someone in senior management that had oversight across all locations that I think we learned a little too late was very much not an effective, healthy manager,” Jenkins says. “They’re no longer in the organization; they chose to leave on their own. But in the process of leaving from Fig, it was their last day, and two days later this starts.”

That turnover is also a sticking point for the unionizing employees.

“We’ve gone through four kitchen managers and four GMs in the last nine months, so the management changes regularly,” says Hughes. “And that is also part of the turnover—it’s not just us turning over, it’s everybody. That’s why it’s so difficult to maintain any kind of stability or anything in the workplace, because it’s constantly shifting and changing, and not in a positive way all the time.”

The turnover reached a critical point on Saturday night, when Jenkins announced via Slack that every employee who participated in the strike had been fired.

“Employees hired with full consent of Foxy’s wages, policies, and workplace philosophies entered three locations and disrupted business,” read the message, which The Savannahian obtained. “They were loud, they upset customers, and they affected everyone involved regardless of their age or standpoint. The disruption that occurred today was not done in good faith and was unlawful. Those who participated in this unlawful disruption have been terminated for that reason.”

Jenkins also added that she was “sad that today happened” and will be amending hours while they look for other employees to fill in the gaps.

Is participating in a strike unlawful? Georgia is an at-will state, which means their employment can be terminated at any time for any reason, as long as the reason is not specifically prohibited by law. Georgia law also forbids mass picketing if the action obstructs or interferes with the entrance to or egress from the building.

Federal law protects employees from being fired after participating in a protected strike against their employer. According to the National Labor Relations Act, a strike is legal if the employees are striking for economic reasons or to protest an unfair labor practice by the employer.

Saturday's strike began at Foxy Loxy, stopped by Henny Penny and ended at Fox & Fig. Photos by Reese Shellman.

What’s next for the Foxy brand? A legal challenge from the USSW and unionizing employee seems likely to follow. The cafés will also reduce hours as they search for new employees.

While public opinion is certainly divided on who’s in the right here, this moment could open up a larger conversation about labor rights for Savannah’s service industry workers—and how those employers should respond.

Note: This story was updated to reflect specific numbers of employees involved in the strike and thereafter terminated.

Please consider helping support our journalism by subscribing or donating today.