By Rachael Flora

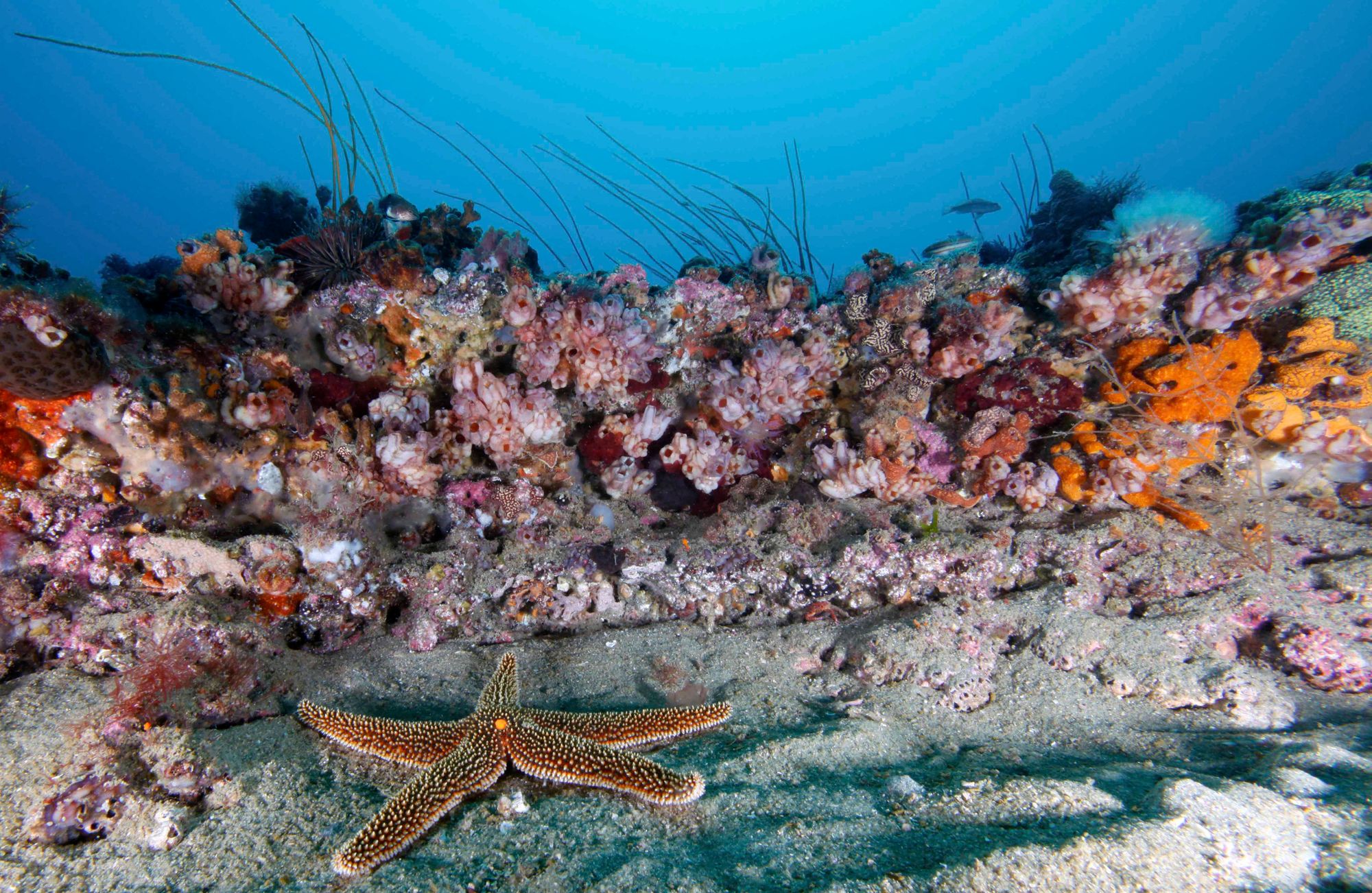

JUST A FEW miles off Georgia’s coast lies Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, a pristine live bottom habitat reef that plays host to many different species.

The 22 square mile reef is just a section of a thriving ecosystem running from Cape Hatteras to Cape Canaveral and is just one of 14 such sanctuaries in the United States. Researchers look to the reef to learn more about the species that live there, as well as how climate change is affecting our ocean waters.

In honor of Gray’s Reef’s 40th anniversary on Jan. 16, we caught up with the sanctuary’s new superintendent, Stan Rogers, about the new and ongoing initiatives to turn Gray’s Reef into the household name it deserves to be.

What compelled you to take this job?

That’s a long story, but I’ll try to make it short! I’m a Lowcountry native. I grew up just across the river in Hampton County, so I definitely have an affinity for the Lowcountry and the coastal islands’ resources we have. I was always inspired to work in the area, and I started out my career doing so, but then my career took me to Colorado and Maryland and DC. When the opportunity came up not only to work with sanctuaries but to work with Gray’s Reef, right in the backyard of the place I grew up in, I was very excited to jump on the opportunity to give back to the community that I grew up in and to help conserve and protect our natural and cultural resources.

What does a day in the life look like for you?

During the pandemic, we have been able to continue doing most of the things we would’ve done. We’ve been out of the office since last March, so we’re approaching a year of remote working. Being able to do outreach with the community, hosting and attending events, has really been impacted. But a lot of the work we do—conserving, planning for science, scientific research—that work continues and has really gone on unimpeded.

Some of our actual internal work, like going out to Gray’s Reef and scuba diving, has been limited since last March. We’re trying to keep our chins up, and we’re back into doing our own work internally.

A day in the life prior to the pandemic would be mixed with working with our communications team on building an educational and outreach-type program with events, spreading the word and gaining awareness about Gray’s Reef as well as our scientific research mission.

Gray’s Reef is a catalyst for research in the part of the ocean we’re in, and we’re trying to understand the live bottom habitat where Gray’s Reef is. We’ve invested a lot of time and effort into scientific research, planning research expeditions on the NOAA Ship Nancy Foster, and our own work with our partners is a big part of that.

We also have resource protection, learning about regulations and enforcement of those regulations. We make sure people are using the sanctuary responsibly. We have a host of recreational fishers and divers that come to Gray’s Reef, so really making sure there’s a pristine habitat for them to enjoy.

How has the lack of in-person events affected your outreach? Has that been difficult for you?

We participated in several outreach events throughout the year, like CoastFest down in the Brunswick area. We’ve been part of boat shows and other outreach events that are partners in the oceangoing industry. We have a strong tradition at Gray’s Reef of being part of the community.

We were also planning for last Memorial Day to host one of our very first expositions that’s really about Gray’s Reef and the work we do. Our team put a lot of effort and heart into that process to make an expo happen, and then the pandemic came along and we had to postpone it.

We hope to parlay that into our next initiative, which is establishing a visitors’ center in downtown Savannah. What we’re working towards now is leasing some storefront-type place to have a place where we can engage better with the public and have science talks and our exhibits on display. We have multimedia galleries and touch tables and 3D goggles to take a virtual dive of Gray’s Reef.

We’re going to build and plan our efforts so we’re better able to reintegrate with our outreach activities to maybe do something around the opening of that. We’re hoping to have a place by the fall and then see when we can actually have an in-person outreach event to celebrate the opening.

What are some of your top priorities in this role?

Expanding awareness about Gray’s Reef has certainly been part of our mission for a long time. Gray’s Reef is a national marine sanctuary, and being so, if you say Yellowstone National Park, most Americans have heard of it. You can generally paint a picture in your mind of what it’s about and what you can experience there. A national marine sanctuary is just an underwater national park. We’d love everyone along the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas and North Florida to know about and go visit Gray’s Reef, but we really want to expand awareness as a national asset, a national place beyond the coast, going inland and making sure people in Atlanta and Jacksonville and Columbia know.

Gray’s Reef is one of 14 sanctuaries, and we want Americans to be aware of the sanctuary system, but for Gray’s Reef to be at the top of the mind in things they know about and maybe aspire to visit one day, or at least learn more about. That’s the biggest thing that’s an ongoing priority, expanding awareness beyond our coast.

Scientific research is one of the major pillars of the work that we do. The sanctuary was designated in 1981, so we just had our 40th anniversary on Jan. 16. We want Gray’s Reef to be the place where researchers from around the world want to come and study and answer the questions we have about live bottom habitats or the species found there. We have great partners, but we want to build on those partnerships and include potential new partnerships as well.

One of the things we’re trying to do is understand visitor use. How many people go to Gray’s Reef each year, and what do they do there? That’s difficult for a site that’s 20 miles offshore. If it was right on the coast, you could go and count people, but we don’t have turnstiles out in the ocean. We use things like satellites and observations from boats and surveys. That’s important to be able to manage people and know how people are using it.

The other is about the live bottom habitat itself, trying to understand the connectivity of Gray’s Reef and how the patch of live bottom reef habitat interacts with other live bottom reefs across the south Atlantic, from Cape Hatteras to Cape Canaveral. We want to know the ecological connections, how fish use that area, how corals propagate and move through that area. We’ve done a lot of research on that over the last several years, and we’re going to continue that.

What’s the significance of expanding that study zone? What does that mean for our area to collect more data about how that stretch works?

Gray’s Reef is 22 square miles. It’s a patch in a large area. It’s a wonderful example of a live bottom habitat, very pristine, wonderful, intact habitat with a low degree of human disturbance. It’s important to have a place like Gray’s Reef, but it’s also important to understand not just how things are in the sanctuary but how the condition of those resources are changing environmental conditions with ocean acidification, with higher ocean surface temperature, things like that. How does this area compare to other areas in the south Atlantic? We’re studying that, not just the animals and how they move and migrate from the sanctuary into these larger areas but also those physical and chemical type parameters as well.

It’s really important with climate change to understand how things are changing, what new species are coming into the area, and what species are now leaving. Now that waters are warmer, are we seeing different species now further north or further south?

I know you’re also working to try to understand the cultural and maritime heritage of Gray’s Reef. Could you talk a bit more about that?

Gray’s Reef itself was designated for the natural resources that are found there, so we don’t have any maritime heritage. That’s a term for things like shipwreck or maritime-associated facilities or industries that may have been associated with a sanctuary. In our case at Gray’s Reef, it’s all about the natural resources. However, Gray’s Reef is an area that was important in the history of our nation, especially during World War II when the Battle of the Atlantic was taking place. You recall the German U-boats off the shore, and the coast of Georgia was really one of the first places where those interactions happened. A few merchant vessels were sunken off the coast of Georgia, some in close proximity to Gray’s Reef. On our maritime heritage front, we’re trying to expand our thoughts a little bit, really just understanding the context of Gray’s Reef.

We’re also trying to understand the prehistoric context. Gray’s Reef was once land—it was once an island and once connected completely to our shoreline. As sea level rises and falls over time, there has been potential human occupation in that area when Native Americans existed there. We do have evidence of artifacts, so that’s very interesting. We also have paleontological resources—we find fossils and mastodon bones and a bison foot and things like that. Things you wouldn’t expect to find 20 miles off shore, 60 feet below the ocean, but in geologic times, this was land and ocean over time, so there’s lots of interesting things at Gray’s Reef.

Because of the designation of Gray’s Reef being about the natural resources, that’s where the majority of our emphasis has been, but these other aspects are also very great stories and a wonderful educational tool so people can understand that things are very dynamic. When you hear about sea level rise and change, knowing these are natural processes that happen, we’re learning with our current set of environmental changes and how it’s changing now.

Can you tell more more about the artist-in-residence program you hope to begin?

I mentioned the visitors’ center being one of our top priorities in increasing awareness of Gray’s Reef beyond our coast. That can take many shapes and forms. One that I’m particularly interested in is transcending science. We talked a lot today about through the lens of science, but how do you view Gray’s Reef or these habitats or oceans through a different lens? How do we engage more people through non-science? If you’re an artist, how do you see the world? How do you interpret the world through your art? To me, that’s very fascinating. It really engages a broader range of our community that may not be scientists or understand the science behind things, but seeing beautiful art or sculpture or poetry about a space can engage a lot of people.

We want to start up our artist-in-residence program in association with our visitors’ center, having a place for that person to be and people to come see their work. Savannah is a great arts community, and we hope to take advantage of that, starting in Savannah but hopefully radiating outwards to be a national or regional program where aspiring and accomplished artists want to be that artist in residence.

It’s also the 40th anniversary of Gray’s Reef. Let’s talk about the significance of that date.

It’s always good to have an anniversary date to pause and think about things, think about where we’ve been and where we’re aspiring to go. It’s not just a date in our mind. We’ll be talking about the 40th anniversary throughout this year, taking time to look back at all the amazing things that have happened with us, our partnerships, our staff, all the great people that have contributed to Gray’s Reef over the years.

We’re painting the path for the future—in the next 40 years, where are we going? That’s leading up to our management plan review in 2024. That seems like a long ways out, but these things take several years to get in place, so really just looking forward as to what Gray’s Reef can be and how people can enjoy it and learn more about it.

That 40th anniversary in my mind is a big deal; we’re going to be talking about that for quite a while.

What are some notable thing Gray’s Reef has accomplished in this 40 years?

We worked with our partners to learn more about how ocean acidification is affecting species that have hard shells that need to build a shell with calcium. Learning about the changing environment has been a big part of what we’re studying—learning about how fish migrate and move through Gray’s Reef.

We have a report called the Decade of Detections where we have tagged various fish and tracked their movements through the south Atlantic for a decade. Being able to see the lines where fish go and how they use different habitats near shore and offshore has been amazing. I think that’s been a major accomplishment to have that report out.

We also have the designation of a research-only area at Gray’s Reef and we’re studying the effectiveness of that to facilitate scientific research and have an area where we’re pretty unique in that Gray’s Reef has a control area that fishing and other extractive areas are not allowed so scientists can study the absence of human activity. I think that’s a major success. We’re going to be publishing more about that, the studies that have been accomplished in that research area.