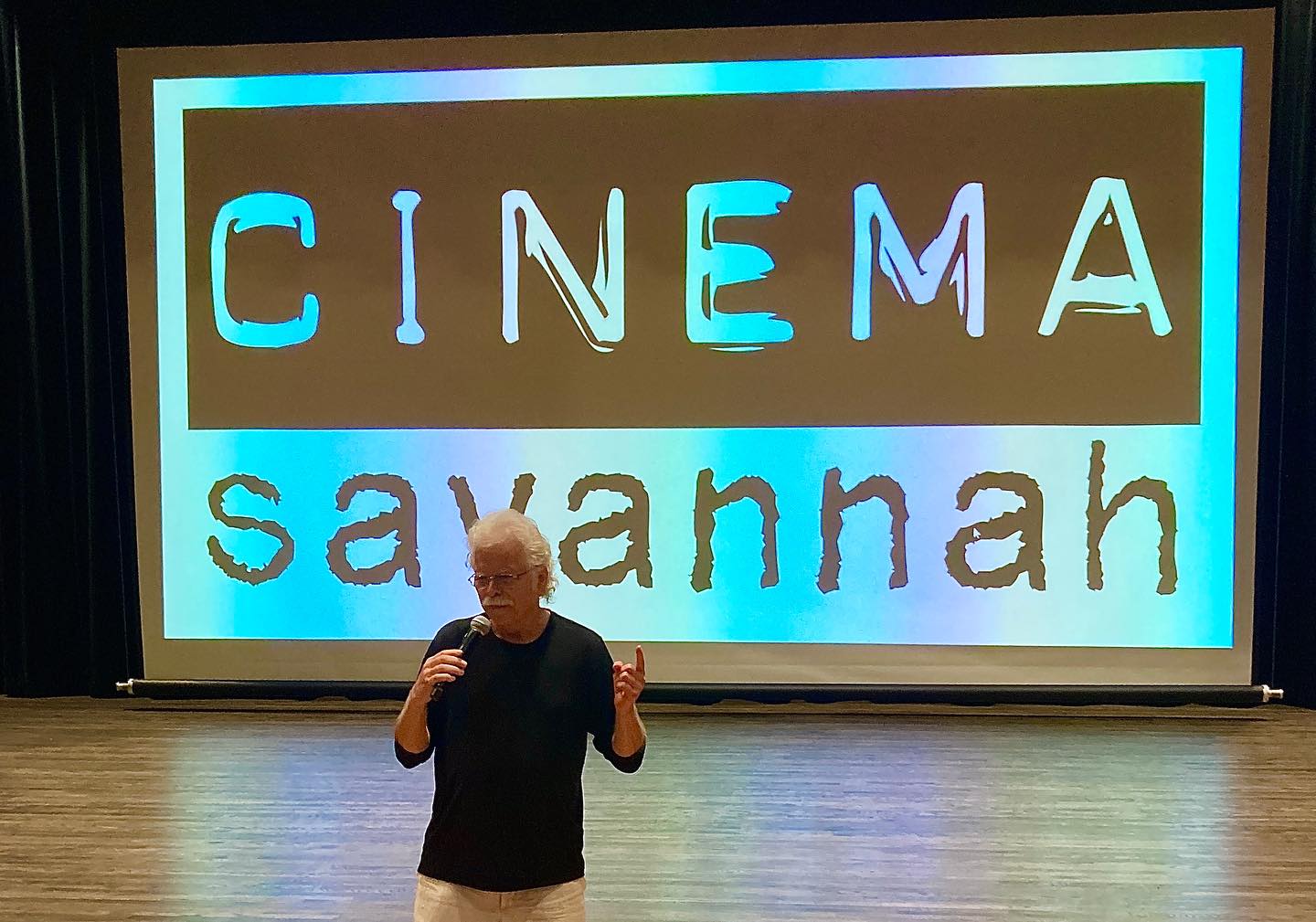

LAST night, the stellar local organization Cinema Savannah screened No Other Land, this year’s Oscar winner for Best Documentary, at the Otis Johnson Cultural Arts Center (formerly Savannah Cultural Arts Center).

For those unaware, No Other Land won the Oscar despite not being able to find a distributor in the United States, due to its graphic, entirely journalistic, and entirely accurate portrayal of Israeli brutality against Palestinian residents of the West Bank.

Very few people in the U.S. have seen the film, and possibly very few will ever see it.

As Cinema Savannah director Tomaz Warchol said to begin last night’s screening, “This must be the only Oscar-winning film not allowed to be seen in the country that gave it the Oscar.”

While 99.9 percent of No Other Land takes place prior to October 7, from roughly 2019-2022, and deals with the West Bank, not Gaza – which are two different places! – nonetheless the “controversy” about this all-too-real chronicle made it untouchable for… well, for U.S. political interests, to put it one way.

Because of the extraordinarily rare nature of this screening – if you didn’t see it last night, it’s possible you will never see it – I wanted to write this review.

I will begin by saying that after you see No Other Land, you understand why the Israeli government doesn’t want anyone to see it!

It’s a nearly total cinema verite look at almost indescribable human oppression. There's no voiceover, no extraneous exposition, and all the cameras are either small handhelds or cellphone cameras.

The film begins with the Palestinian residents of Masafer Yatta having about 15 minutes warning to completely vacate their ramshackle homes with any possessions they can grab, before a unit of Israeli army bulldozers comes to crush and demolish their houses and anything still left inside them.

The residents yell and curse at the Israeli soldiers, most of whom are robotically impassive unless a rock is thrown their way. The children cry and don’t understand why their home is being destroyed. The parents are left to try and explain it to them.

The reason always given for the sudden, unannounced demolition of entire neighborhoods is “this is now a training zone for the army.”

But as we soon see, it’s really just the army clearing land for illegal Jewish settlements, which are allowed to happen in a wink-wink, look-the-other-way manner.

Every time the Palestinians rebuild, the bulldozers come again. And again. The residents spend a lot of time living in ancient caves in the surrounding hills, which gives the film a surreal quality.

When they try and rebuild, sometimes the Israelis take away their building tools. Much of the film revolves around the tribulations of Harun Abu Alam, shot by an Israeli soldier and paralyzed from the neck down while resisting having his tools stolen by them.

Then the Israelis take the Palestinians’ electricity away, then their generators.

Then… the Israelis take their cars.

So this is ethnic cleansing with a twist: Palestinians aren’t allowed to have a home, but they're also not allowed to leave – doomed to be chased by soldiers and bulldozers across the desert seemingly for eternity.

The cruelty is the point.

In one particularly heartbreaking scene that drew gasps from the audience, in a deeply symbolic crime against both humanity and the environment, the Israelis force Palestinians away by pouring cement in their only water well, here in the dry desert where water is so scarce.

Against this backdrop, the human story centers on the filmmakers: a young Palestinian man, Basel Adra, and his Israeli journalist friend Yuval Abraham.

Basel is an affable, good-natured person of enormous courage and endless patience, who describes himself as an activist because he frequently posts photos and video of the situation in the West Bank.

Basel is entirely relatable in the way he constantly checks views and comments of his posts. He occasionally laments that no one outside the West Bank cares what happens to them.

Yuval, while clearly sincere in his own pro-Palestinian activism and journalism, is never completely trusted by the villagers because he is Israeli.

But they are a deeply hospitable people despite their anguish, and if Basel accepts Yuval, that seems good enough for them – though they do frequently take the opportunity to remind him that he can always leave anytime he wants to, unlike them.

While there has been a certain amount of low-key controversy about how No Other Land was introduced to America at the Oscars – with Yuval as the main marketing point since he speaks English – to be fair, Yuval shows a different, but entirely valid, form of courage of his own.

As an Israeli in a nation politically obsessed with the destruction of Palestinians, he is an outcast from most of his countrymen. We see this in one Hebrew-language clip from an Israeli TV interview he does with a right-winger, who questions Yuval’s patriotism and Jewishness.

It’s impossible not to feel sorry for him as well, and to admire his courage.

At one point a Palestinian man says, “We are strangers in our own land.” In a sense this describes Yuval as well.

While Yuval can indeed always “go home” to a comfortable apartment in Israel, it’s possible that he has less sense of community than the Palestinians he admires, who all live closely together in tight-knit and loving multi-generational families.

I always hesitate to compare the plight of Palestinians to any other global struggle, since their struggle is so harsh and unique in so many ways, and never gets nearly enough attention on its own.

But as an American, a white Southerner in particular, it was simply impossible for me to watch No Other Land and not be vividly, crushingly reminded of how Black people were persecuted and brutalized in this country.

Like Black people fairly recently in our own history, these Palestinians also have no civil rights and no voting rights. They can be shot at will by soldiers or police, with no legal recourse.

Palestinians have to drive on separate roads, i.e. segregated facilities. Their vehicles have different color tags to separate them – green for Palestinian cars, yellow for Israeli cars.

All this is the exact definition of an apartheid, segregated state. If you say otherwise, then you’re saying those words have no meaning at all.

The fact that most of No Other Land takes place coincidentally at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement only makes the comparison more stunning.

At one point, we see an Israeli soldier with his knee on the neck of a prostrate Palestinian child. Can’t get any more visceral a reminder than that.

The analogy to the United States is most disturbingly stark in a scene where Israeli settlers mount what can only be described as a racist terror attack on the Palestinian villagers. With no warning, they set upon them with rocks and clubs, some with firearms, just to destroy their property and terrorize them.

Israeli soldiers look on passively, clearly there to protect the settlers from reprisal. While the soldiers at least operate under some sense of order, the settlers are uncontrollable in their racist hate.

The fact that the violent settlers wear long, white cloth masks, i.e. white hoods, to hide their identities makes the direct analogy with the KKK clear.

On a positive note, I was struck with the remarkable patience and resilience of the Palestinian residents in the face of such endless cruelty.

The children continue playing children’s games, the families continue laughing and joshing each other, the men continue gathering around at night smoking a hookah, shooting the shit.

While I’m tempted to say they are much more patient than I would be in the same circumstances, the truth is it’s probably precisely this devotion to community and to family that keeps them alive and gives them hope in the long run.

The film doesn’t really have a “conclusion” per se, since everything that happens is still going on today, except further exacerbated by the aftermath of Oct. 7.

One is left wondering: As terrible as it is for Palestinians in the West Bank, having to deal with bulldozers and rifles and clubs – how much worse is it for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, being attacked by 2,000-lb bombs and airplanes provided by the U.S., and tanks, and white phosphorus shells, and drones, and snipers?

As the lights went up, not a sound could be heard. What we’d seen and felt was just too intense for words.

I think most of us will still be processing this film for some time to come.

Kudos to Tomasz and Cinema Savannah for having the courage to do the right thing, and finding a way to bring No Other Land to a local screen.