By Rachael Flora

THE STRUGGLE to find affordable housing in Savannah is not a new one, but it’s become a hot topic after last month’s purchase of the Chatham Apartments.

The 69-year-old building, formerly a low-income housing complex, was sold last October to QR Capital, an Atlanta-based real estate company that aims to “acquire, renovate and operate conventional multifamily and student housing projects.” QR Capital then sold the building to SCAD last month for $39 million.

When QR Capital acquired the property, they displaced more than 200 residents, some of whom ended up becoming homeless. The company did provide assistance in relocating the residents.

Still, the sale seems to exemplify the way things have been going in our town for a while now: locals lose out to whatever developer has the most money. Add the thriving pandemic and the skyrocketing unemployment rates, and the situation feels urgently terrible.

However, affordable housing has been, and continues to be, a struggle in Savannah. In this special report, we take a look at why we lack affordable housing, how it affects Savannahians, and how we can provide housing for more people in our community.

GIVEN THAT Georgia’s legal minimum wage is $5.15 an hour, many Savannahians live in poverty—a third, to be exact.

“One out of three households in Savannah containing children are asset poor, meaning they don’t have enough money on hand for an emergency or to meet daily needs,” explains Alicia Johnson, executive director of Step Up Savannah, a nonprofit dedicated to economic opportunity.

Georgia's minimum wage is so low that the Federal Fair Labor Standards Act applies, so employees must earn a minimum wage of $7.25 an hour.

But Savannah’s poverty wage, or the federal threshold for being in poverty, is $12.32 an hour. Many Savannahians make much less than that.

What exactly, then, is housing that’s affordable for the average Savannahian?

I used the $12.32 wage, along with the general rule to spend 30% of your income on housing, to find that affordable housing at that wage would be $675 a month. That, of course, doesn’t take out taxes and assumes that the job is full-time. Still, I rounded up to $700 a month when searching online for apartments.

I looked specifically for apartment complexes and excluded individual listings in my search.

What I found was pretty bleak: Savannah has about a dozen apartment complexes offering rooms that cost under $700 a month.

There are also eight public housing complexes, as well as several affordable senior homes, but the waiting lists for those complexes are closed.

According to 2018 data by the Chatham County Housing Coalition, there are 13,173 Savannah families on the waiting lists for public housing and the housing choice voucher.

Alison Slagowitz, a staff attorney for the Georgia Legal Services Program, says it’s a special event in her office when a spot opens up on the public housing waiting list.

Lana "DiCo" DiCostanzo, program manager at Deep Center, remembers trying to get into Savannah Gardens housing. She'd have to go to the complex each morning to ask if any spots had opened up overnight.

"No one has time to go through these systems," she says. "You're putting barrier after barrier for me to be able to function on a day-to-day basis."

So, while thousands of families wait to get into public housing, they can choose from twelve apartment complexes, many of which are listed as unavailable on websites like Zillow.

In comparison, a search for apartments in Savannah on Zillow yields over 180 results. According to lowincomehousing.us, the median apartment rental rate in Savannah is $1,119.

It’s important to note that with affordable housing, one size doesn’t fit all. As limited as our options for subsidized or public housing are, so too are our options for everything between that and luxury apartments. Put more simply, you don’t have to be poor to not be able to afford housing in Savannah.

"It's interesting that when we talk about it, we just talk about it in this black and white, 'affordable housing is just project housing or mixed income housing,' and we have that problem solved," says DiCo. "No, there are so many layers to that."

Formed in 2018, the Chatham County Housing Coalition looks at the full spectrum of affordability in housing, from very low income to workforce to moderately priced homes. All these types of housing are necessary to supporting our community.

The lack of affordable housing in Savannah is, according to Mayor Van Johnson, because we’re long overdue for a plan.

“We’re finding that many of our citizens who love Savannah have to live in other municipalities or other counties, just because Savannah’s not affordable,” he explains. “A lot of that is market-driven. We really did not have affordability in mind when we let the market do what it did, but we didn’t have a plan. Hence, we’re in this situation where rent is high, mortgages are sky high, and the average Savannahian cannot really live in Savannah anymore.”

What Mayor Johnson refers to, of course, is the development of downtown, most notably the hotel boom in the past several years. Tourism has taken over the downtown sector. It’s hard to tell when it happened, but everything north of the park has been steadily pandering to tourists for some time now.

And it’s bringing the city money: Visit Savannah estimates that 14.8 million people visited Savannah in 2019, which generated $3.1 billion in visitor spending.

Another important revenue stream to consider is that of the hotel/motel tax. In the same report, Visit Savannah reports $27.7 million in revenue from the 6% tax levied on each hotel.

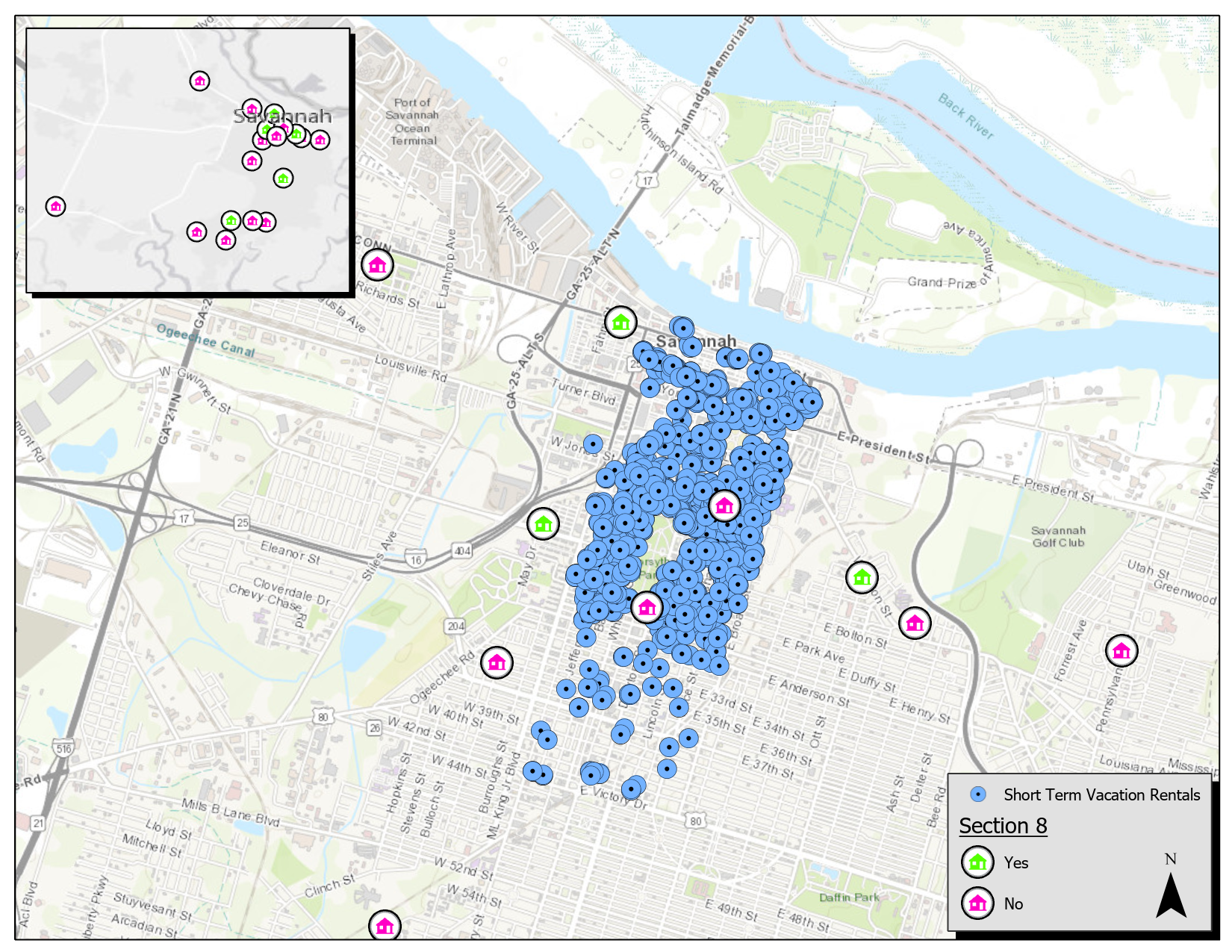

Who else is required to remit the 6% tax? Short term vacation rentals, which have also grown exponentially since they were approved in 2014. There are nearly 1,450 licensed STVRs downtown, largely concentrated to three square miles between Bay and Victory and MLK and East Broad.

It’s been documented that Airbnbs drive up rent prices in the cities they populate.

In a 2019 study published in Harvard Business Review, three researchers found that Airbnbs have driven up rent prices in cities that experience a boom in them, finding that a 1% increase in Airbnb listings is casually associated with a 0.018% increase in rental rates and a 0.026% increase in housing prices.

Long-term, Airbnbs contribute to a fifth of the average annual increase in U.S. rents.

One situation presented in the Harvard Business Review paper is that landlords may begin to switch their properties from long-term to short-term rentals if that proves more lucrative. I spoke to one person in Savannah who reports that as being just the case.

When her landlord sold the property (without notice), the new owners chose to turn the Starland-area space into Airbnbs, so the tenants were given until the end of their lease to find new accommodations. A few tenants were on a month-to-month basis, so they had to scramble to find something new. No help was offered in moving out, though the new owners did allow lease extensions.

“The hardest part was finding something affordable to move into,” she says. “Despite so many properties being available because SCAD isn’t here right now, no one was willing to budge on rent prices.”

It’s clear that we’ve gotten ourselves into a tricky situation with tourism: it pays our bills, but it doesn’t take care of the people that live here.

“You become Hilton Head, where people can’t afford to live,” says Mayor Johnson.

WHEN HOUSING PRICES skyrocket, real people are affected.

Cindy Murphy Kelley, the executive director of Chatham Savannah Authority for the Homeless, estimates that there are roughly 5,000 homeless adults and 1,000 homeless children in Chatham County.

“What became very clear is that we as a community were spending all kinds of time talking about homelessness, which is a symptom of a broader issue, and the fundamental issue was lack of affordable housing,” says Kelley. “We have about 900 people each year who we consider chronically homeless—by far the most expensive, most high-risk residents we have.”

A 2017 study by the National Alliance to End Homelessness estimates that a chronically homeless person costs taxpayers over $35,000 a year due to jail and hospital costs. That number decreases by nearly half when that person is placed in supportive housing.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis have also affected evictions. Currently, Georgia doesn’t have a moratorium on evictions or utility shutoffs, placing the responsibility on the courts to provide discretion.

Even in pre-COVID times, Savannah’s eviction rate was bad: a 2017 assessment of fair housing in Savannah found that tenants only win about 10% of dispossessories.

Interestingly, that same assessment couldn’t find any landlords or housing developers that were not white. It’s important to understand how disproportionately people of color are affected by the lack of affordable housing.

“Our asset poverty rate is 35%, and what you’ll find is that those households are usually African-American females, single head of household with multiple children,” says Johnson.

Additionally, the national average for homes with zero net worth is 16.7%, but in Savannah, Black households with zero net worth is at 30%, and Latinx households with zero net worth is at 27%.

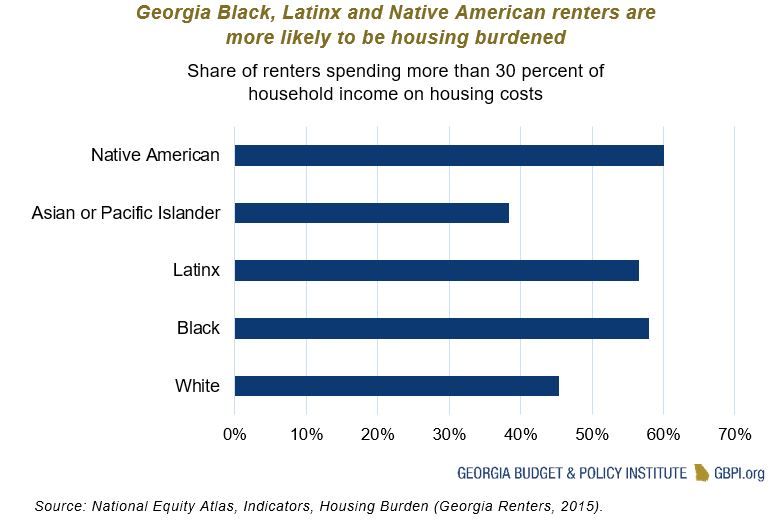

Georgia Budget and Policy Institute found that in Georgia, Black, Latinx and Native American renters are more likely to be housing burdened, or paying more than 30% on their income on housing.

The application process to get into affordable housing can be subject to prejudice and racism.

Slagowitz says that Georgia first drafted its eviction laws during Reconstruction, right after the Civil War, and amended them during Jim Crow.

“This is how the whole generation [of Black people] got involved in the criminal justice system, whether they did something or not, and kept in poverty, kept with unstable living conditions to the point where it’s, ‘Well, the only way we can make money is doing illegal things or being super religious or something,’” says Slagowitz. “They’re free people, but they’ll be second class citizens—three fifths of a person.”

The effects of the policies that originated during Jim Crow are still felt today: redlining, gentrification, and housing discrimination contribute to keeping people of color at a disadvantage.

Slagowitz shares a story about an elderly client of hers who was living in Chatham Apartments prior to its sale. When the developers came in, they provided him with a housing voucher and helped him seek alternative housing. However, he was rejected from at least one complex because of his past: he had a drug-related offense from 1983.

“If you paid your dues to society, why is that a life sentence? If your sentence is over, you get to vote again, you’re not disenfranchised anymore, why can’t you get a place to live?” asks Slagowitz. “And if you don’t have housing, you can’t get a stable job, and what happens to the recidivism rate then?”

Another effect of a lack of affordable housing is transportation. As mentioned, much of the affordable housing in Savannah has been pushed to the outskirts of town.

Before the development of downtown, much of the affordable housing was centered around the core historic areas, remembers Caila Brown, executive director of Bike Walk Savannah.

“But as costs started rising for homes and apartments in the downtown area, people started getting pushed further out to the edges,” she says. “We’ve run into this issue where people need to then take whatever money they’re saving on having a more affordable apartment or purchasing an affordable home. And that savings is completely negated because they have to purchase and maintain a motor vehicle.”

According to AAA, it costs over $8,500 annually to properly maintain and operate a motor vehicle. Many people simply can’t afford that expense, but as more people are forced to move further from their jobs, a commute is unavoidable, and biking isn’t always safe.

“It all just starts adding on,” says Brown. “Maybe you can access the grocery store, but we haven’t built our communities to be those dense, walkable, bikeable ares where you don’t each rely on a motor vehicle. And we created those problems, and then we complain that there’s too many people in the road.”

The baby boomer generation is increasingly affected by homelessness, which poses unique issues for a generation that needs more frequent doctor visits.

"Being out on 204 is really inaccessible for someone who's 65 and needs access to a bus stop or a grocery store, or even a sidewalk—something they can utilize in a safe area," says DiCo.

In her experience, DiCo also noticed that the young people in her programs were spread out over the city.

"When we did Block By Block, very few kids lived in proximity of where we ran programming," she says.

Fortunately, the people in charge of public transit in Savannah understand the importance of a comprehensive bus route.

“We strive to not only move people to their physical destination, but also to help them reach a better quality of life,” said Bacarra Mauldin, CEO of Chatham Area Transit, in a statement. “And that applies to all residents, no matter what their income level. All residents stand to benefit from using our services, just as all Savannahians benefit from having a variety of healthy and safe housing opportunities within their community.”

Access to safe housing has the ability to change lives.

“Studies have shown that when there was affordable housing in play, not only does it boost or change economic outcomes, but it’s overall wellbeing,” says Johnson. “There’s health outcomes, the crime, the domestic violence—all those things are interrupted when there’s sustainable housing."

“IT'S A multiplicity of issues that come to play and solve the problem,” says John Neely, chair of the Chatham County Housing Coalition.

The group, formed two years ago with a variety of community experts, seeks to bridge the silos that exist in affordable housing advocacy and make things happen.

Predictably, one of the largest barriers to creating affordable housing is money. Neely praises the Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program, which offers developers a substantial tax credit for agreeing to keep rent costs at 80 to 100% of the median income.

However, the tax credit funds are limited and disbursed through the entire state, so it’s a competitive program. Neely estimates that one in three applications get funded each year.

“We should probably be creating 1,000 to 1,500 units per year through that or various programs, and we’re doing probably 300 to 500 units a year,” he says.

Currently, the City of Savannah has the Dream Maker Home Buyer Assistance Program to assist citizens in making down payments on housing.

There’s also the Savannah Affordable Housing Fund, established in 2011 to assist low- and modest-wage workers through low-interest loans or grants for emergency repairs.

Neely and the Chatham County Housing Coalition would like to see a funding increase to the affordable housing fund in the 2021 budget, for which budget hearings were just held.

“Instead of $150,000 per year, we’d like to see them allocate half a million to a million per year,” says Neely.

DiCo points out that for a long time, the apartments in the public housing complex Yamacraw Village had mailboxes without doors on them.

"If places like that take so long to replace just a door, why are we able to build luxury housing within a month?" she asks. "Why do we not put in the money to renovate Yamacraw?"

It’s also important to work on turning existing structures into affordable housing. Brown points out that a building like the 69-year-old Chatham Apartments couldn’t be built again.

“We have so many arbitrary zoning laws that if you built Chatham Apartments today, you would need to have a surface parking lot with a hundred spaces in it,” she says. “We’re creating this reliance on motor vehicles, which exponentially increases those costs.”

Mayor Johnson has been working on clearing blight and cloudy titles, particularly on the westside, to build market-rate homes. He sees housing stock as one of the most significant barriers to affordable housing here.

“Savannah’s been around since 1733. There’s not a whole lot of land development,” he says. “Dealing with the lack of affordable land, land prices go up, construction prices go up, and it’s hard to keep the affordability in check.”

The Chatham Savannah Authority for the Homeless has created a unique solution to development: tiny houses.

Through The Tiny House Project, homeless veterans are able to move into small, permanent homes for just $240 a month, utilities included.

Kelley explains that it’s crucial to create housing for the chronically homeless as a way to support them, but businesses make no significant profit off that kind of development.

“What we need to do is have a stronger nonprofit sector that provides that kind of housing development,” she says, “and the Tiny House Project was developed with that in mind.”

Kelley admits that it was tough at first to get the project off the ground, lacking support from both city government and NIMBYs, but the Tiny House Project is now in its second stage and has 23 homes.

“I’d love to see our local homeless nonprofits consider becoming community development corporations—and that’s just a fancy way of saying they develop housing—and consider taking on those smaller units and make them available as affordable rental units,” says Kelley.

The Tiny House Project exists on Wheaton Street, but Kelley’s suggestion of developing homes within the city would help keep transportation costs down and get back to an accessible city plan.

“At CAT, we support the development of more affordable housing that is also transit-oriented,” said Mauldin. “This means the development would not only support public transit, but also create pedestrian-friendly communities that are within walking distance of jobs, shopping and community services.”

However, as Kelley experienced with NIMBYs, not everyone is welcoming of disadvantaged people in their neighborhoods. Last week, Savannah’s City Council delayed a vote for the Salvation Army’s proposed transitional housing project for the homeless. The shelter, slated for District 1’s Augusta Ave., didn’t have the support of its alderperson, Bernetta Lanier.

“Why would you take one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city of Savannah, and plop the homeless shelter right down in the middle of it?” asked Lanier, as reported by WSAV.

There seems to still be a stigma attached to people in need of low-income housing. That’s a problem that Slagowitz sees in her line of work.

“We should work towards eliminating frivolous and meritless barriers to accessing affordable housing,” she says.

A big part of that is reentry housing, which Mayor Johnson is also working on with his task force Advocates for Restorative Communities of Savannah.

“Outside of Fulton County, Chatham has the largest number of people returning home from jails and prisons,” he says. “When they come back, one of the challenges is finding a place to live. If you don’t find ways to make people successful when they come home, they go back to doing what they know.”

With this task force, Mayor Johnson looks at workforce and reentry housing to help ease people back into life outside of jail.

WHEN LOOKING AT a problem as big as the lack of affordable housing in Savannah, it can seem like an insurmountable problem, one that relegates our city to nothing more than a tourist town, devoid of local flavor—and anything local at all.

But as grim as the outlook may seem, Savannah has a wealth of people working hard to make affordable housing a reality and support the community that lives here. It’s all about working together now.

“Most of our social safety net here in Savannah is directed at the tyranny of the moment,” says Johnson. “This person’s hungry, we’re going to give them food. This person ins homeless, let’s try to work on sheltering them. But we have fewer programs or collaboratives that are aimed at breaking that full cycle of what poverty looks like. That’s why affordable housing is so important.”