By Rachael Flora

AFTER the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in the summer, abortion has become one of the biggest issues on the ballot—particularly statewide, as the legality of abortion is now up to the states to decide.

To recap: Governor Brian Kemp passed a bill, HB481, outlawing abortion after six weeks of pregnancy in 2019. The bill was blocked due to Roe’s protection, but the Dobbs v. Jackson decision removed federal protection to the right to have an abortion and left that choice to the states, so Kemp’s bill was immediately moved through the legislature (thanks to Attorney General Chris Carr, who is also up for reelection) and became Georgia law.

I wrote a three-part series on abortion access in Georgia last year, in which I spoke with medical professionals who have performed abortions or assisted afterwards. Their livelihoods have been at risk for a while—Denise, a doctor who performs abortions, told me that she knows some doctors who have been ostracized in their community, let alone the ones who are harassed simply going to work. Now, in some states, abortion providers have to worry about legal threats in addition to physical violence.

Since Roe v. Wade was overturned, abortion access in Savannah has dwindled: the Savannah Medical Clinic closed its doors shortly after the Dobbs decision, and now the only place offering abortion care in Savannah is the Planned Parenthood Health Center.

(A quick Google search of “abortion in Savannah” will yield results from Thrive Savannah; this is a religiously-affiliated organization that lies to and misleads patients to get them not to choose abortion. In my series last year, Madeline told me that she had patients who received a fake ultrasound and were told that they were less far along in the pregnancy than they really were, under the guise of giving them time to decide what to do, but by the time they ended up at her clinic, they were too far along to get an abortion. These are the same people in the big pink bus that shout at patients outside the Planned Parenthood.)

In the few months post-Roe, there have been several horror stories about patients needing to cross state lines to receive abortions, like the 10-year-old girl in Ohio who was a victim of rape and had to travel to Indiana to get an abortion. (That doctor, by the way, was harassed by people upset with her for performing the abortion.)

But according to one CNN report, abortion providers are being told by hospital leadership not to speak publicly about what they’re seeing at work.

The outrage over this decision exploded over the summer, with marches and actions and social media posts galore. But will this issue be a top priority for voters on Nov. 8—and is it pressing enough to turn people out to the polls?

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll conducted by UGA’s School of Public and International Affairs showed that the biggest concerns to voters, in order, are the cost of living, threats to democracy, and jobs and the economy. Abortion appears pretty far down the list, with only 5% of respondents saying it was a top issue and 10% calling it a second-most important issue.

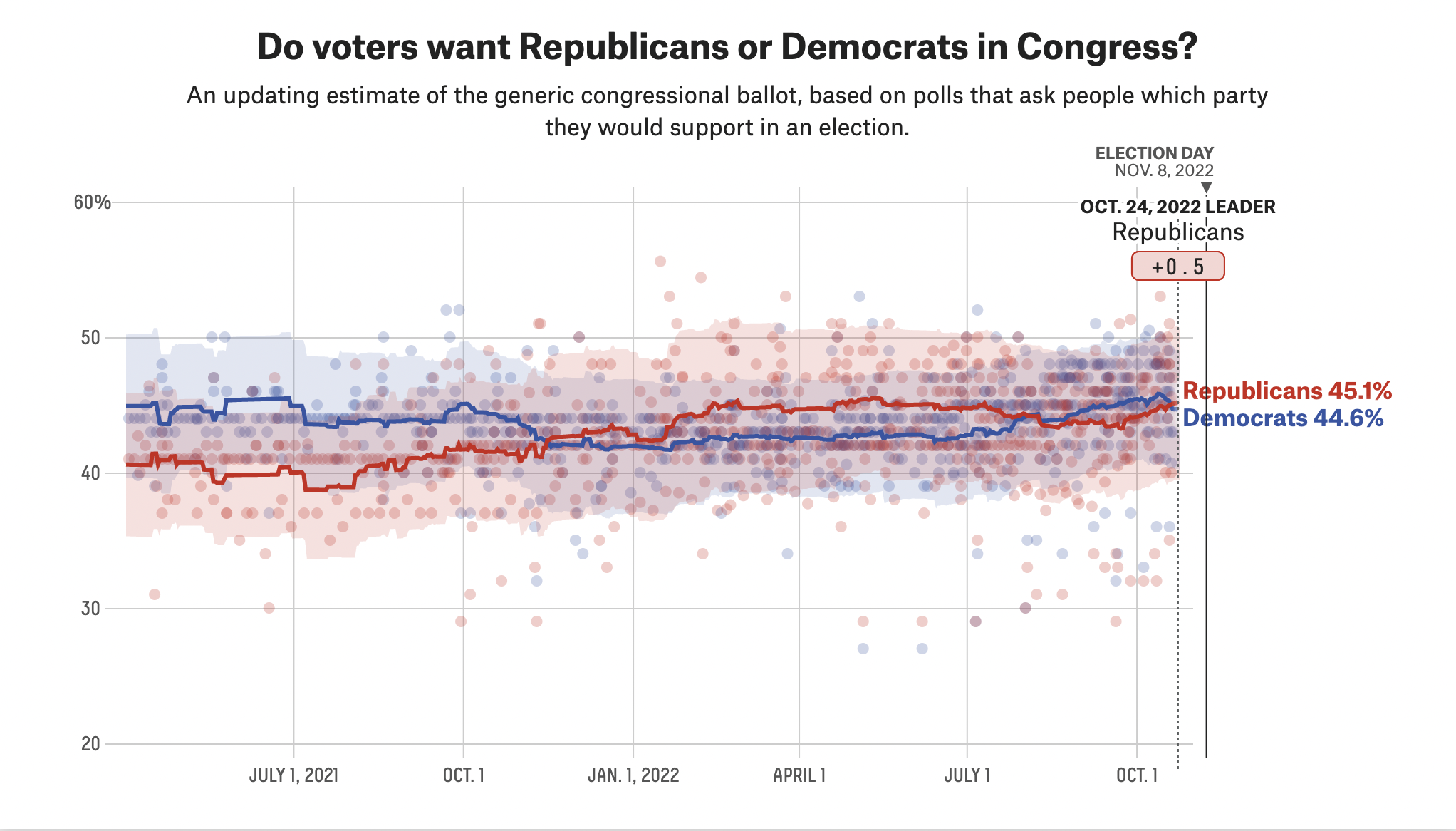

The polls don’t show Democrats with a walk-off win by any means, even nationwide: FiveThirtyEight has a poll showing favorability for Republicans and Democrats in Congress. A week ago, Democrats were up 0.3 over Republicans; today, that number has flipped, with Republicans up 0.5.

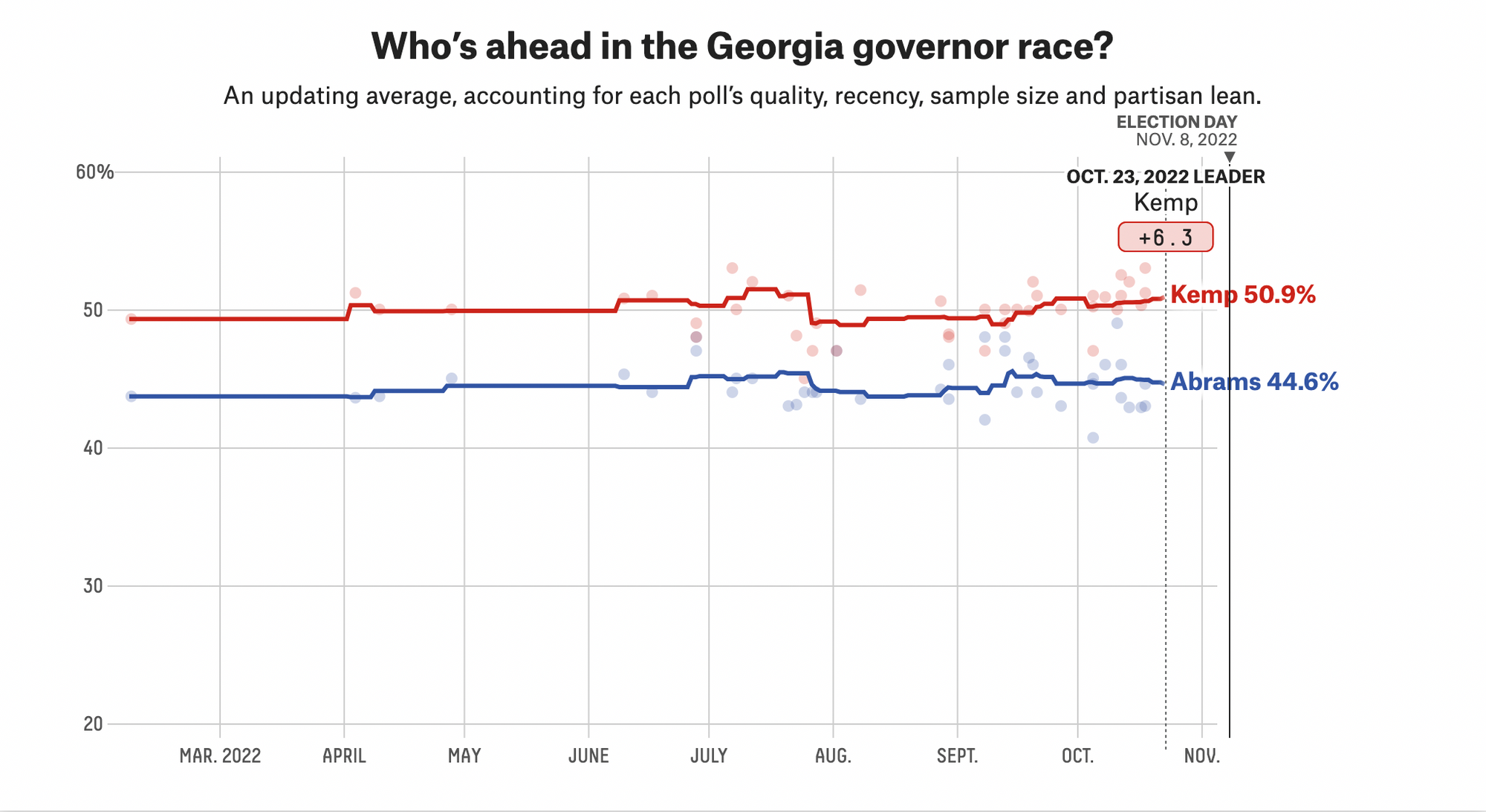

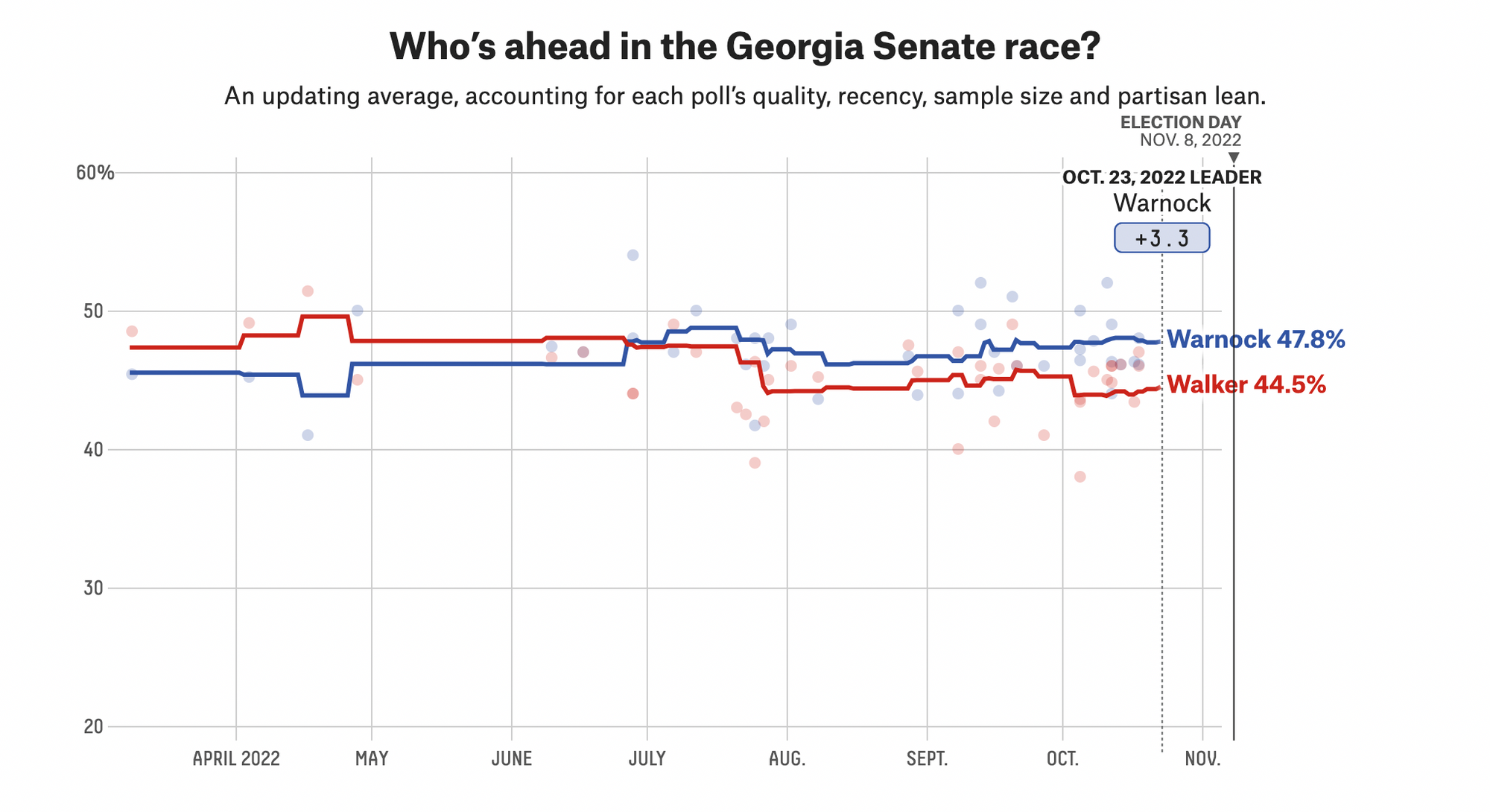

The same site shows Kemp up 6.3 points over Abrams, but Senator Raphael Warnock up 3.7 over Herschel Walker.

Walker, by the way, has not suffered any major setback for the bombastic revelation that he paid for a girlfriend’s abortion, as extensively reported by the Daily Beast. FiveThirtyEight estimates that the dust-up lost Walker some support, with polls showing Warnock pulling slightly ahead. Despite being the embodiment of hypocrisy on this issue, he hasn’t lost any favor with fellow Republicans: in our interview with Rep. Buddy Carter, he said of Walker, “I believe that Herschel Walker will be the next Senator from Georgia … I have no reason to question Herschel Walker, and what he has done in his past, that’s not my place to judge him.”

Kemp gave a similar answer when asked about Walker’s abortion story: “I’m going to vote like everyone else, but I’m supporting the ticket. We’re working hard to help the whole ticket in this state.”

This is really nothing new: Republicans have long touted themselves as the party of family values, but fail to support basic social services that would help lower-income families.

That’s a point that Abrams attempted to make on MSNBC last week: “Having children is why you're worried about your price for gas. It's why you're concerned about how much food costs. For women, this is not a reductive issue. You can't divorce being forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy from the economic realities of having a child. It's important for us to having both/and conversations.”

She immediately drew ire from Kemp and other Republicans for suggesting abortion was the solution to inflation, yet she’s correct in that having a baby is expensive: the average hospital bill for giving birth alone is over $14,000, in a state where 19 rural hospitals closed in 2020 and the maternal mortality rate is the second-highest in the nation.

A WABE report estimates that the very first year of a baby’s life will cost parents about $25,000, and you’re in for seventeen more years of that at minimum. As rents continue to skyrocket and the minimum wage continues to be $7.25 an hour, it is simply unfeasible for many parents to adequately care for children.

When I interviewed Denise last year, she said something similar: “Absolutely nobody talks about the cost to the state and the taxpayers about this. For 90% of these women, those pregnancies will be covered by Medicaid. The pregnancy is covered by Medicaid and the children are covered through the state-sponsored health plans. The next thing is the size of the kindergarten class. If you figure that [there are] 30,000 more children a year, it is not an insignificant burden on the existing system. 50% of counties in Georgia do not have an OBGYN doctor. What’s supposed to happen? They’re closing all the rural hospitals because they can’t make it. They would have been able to make it if Georgia had chosen to expand Medicaid based on the subsidies that were provided by the federal government. Who pays for those children?”

Abrams’ own position on abortion has changed: she grew up in a very religious household where she felt that abortion was wrong, but in college she came to see that abortion is a medical issue, not a political or social one.

That’s a pretty common experience among people raised in Christian households and indicates a paradigm shift on how the issue is viewed, not a change in religious beliefs. Abortion is a deeply personal issue that for pro-lifers is steeped in personal and religious morality. That’s largely why a popular Republican talking point is that pro-choice people want to rip babies from their mothers’ wombs the day before birth: that’s factually incorrect, but it evokes such a visceral reaction in the deeply religious that it can be very difficult for them to see differently.

In our conversations, Denise urged me to take the morality out of the issue. The deeply religious people will never change their minds, and fighting anyone on their morality is a losing game. Instead, educating people on the science behind the procedure can change the way they view abortion, as it did for Abrams.

Now, Abrams' position on abortion could basically be "anti-Kemp" and still garner the Democratic vote (and what one could argue is the Democratic strategy this cycle anyway), but specifically, she doesn't support any government restrictions on abortion. Her website says she would work to repeal Kemp's abortion ban, but her ability to do that will largely depend on who else is voted into office this cycle. As mentioned above, Attorney General Carr, who worked quickly to make HB481 law, is facing Jen Jordan in his own election. In September, an AJC poll showed Carr with a sizable lead of 45% to Jordan's 35%.

Of course, polls don't mean anything without votes to back them up. What's the voting landscape looking like right now?

Early voting so far in Georgia has been record-breaking: on the first day of early voting, over 131,000 people cast a ballot, which is an 85% increase from those numbers in the 2018 midterm election and rivals the day-one early voting turnout in the 2020 presidential election. Midterm elections usually see lower turnout, so this response is certainly better than expected and says a lot about voter enthusiasm.

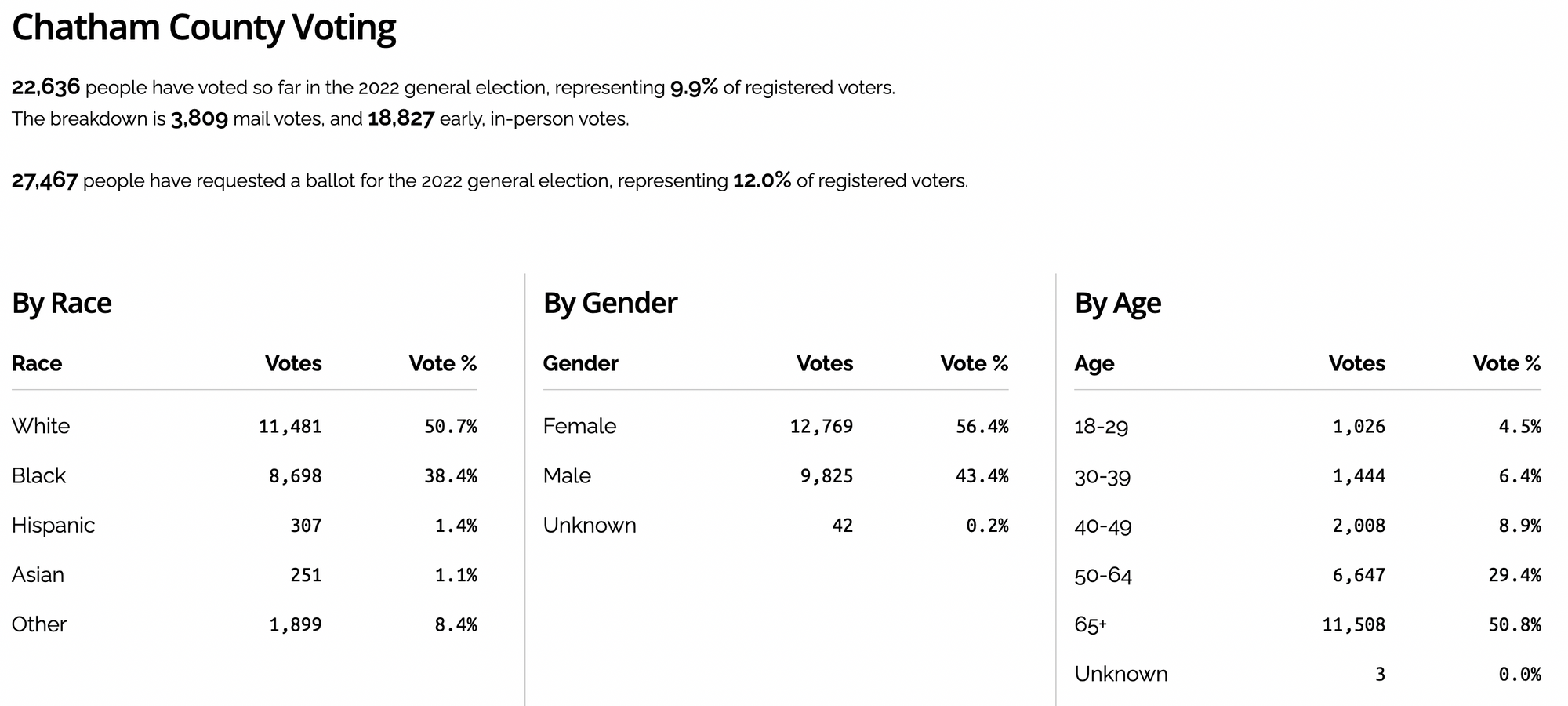

That number is across the state, however; according to Georgia Votes, Chatham County’s early voting numbers are not as encouraging, with only 22,636 people—or 9.9% of registered voters—having voted so far. The senior citizen crowd is carrying our early vote count at this point, with 50.8%, or 11,508, of early voters being ages 65 and up.

It's not quite the youth turnout that Democrats were banking on: pundits have been speculating since the summer that young voters would be mobilized to action by the loss of Roe v. Wade, given the uproar on social media in particular. (Rosie's piece on youth voters this week dives deeper into this issue.)

What will the final numbers look like? With a week and change left in early voting until Election Day on November 8, will more voters turn out to try to preserve abortion access? The answer is yet unclear, but with so many neck-and-neck races across the state, even with an issue as big as abortion, this Election Day will be certainly one to watch.